As I’ve explained elsewhere – and additional studies have confirmed – running back is the most valuable position in fantasy football. As such, it’s crucial you draft the right running backs. More than any other position, it could be the difference between winning or losing your league.

But who are the right running backs in 2020?

Here’s where things get tricky. My quarterback strategy is pretty simple – wait until your league-mates start drafting backup quarterbacks, and then pick your favorite from whoever is leftover. For wide receivers, my strategy is no strategy – grab the best values you can find. Running back is quite a bit trickier.

TL;DR – Bell-Cow or Bust. With few exceptions, draft (or at least prioritize) only bell-cow running backs or running backs with bell-cow potential. Fade just about everyone else. Note: This article assumes PPR scoring for a typical 12-team 1QB start/sit league. The “Bell-Cow or Bust” strategy would be less powerful in a standard league (rather than PPR league) and possibly suboptimal for a best ball league.

Definitions

There are essentially only three types of draftable running backs in fantasy football:

The Bell-Cow Running Back

Every-down players, used as both runners and receivers, ranking highly in snaps, carries, targets, and red zone opportunities. Without much in-position competition, they’ll also rank highly in snap%, carry%, and target%. Whether the team is winning, losing, tied, or in the red zone, a bell-cow running back will still excel in all of these stats.

A Committee Running Back

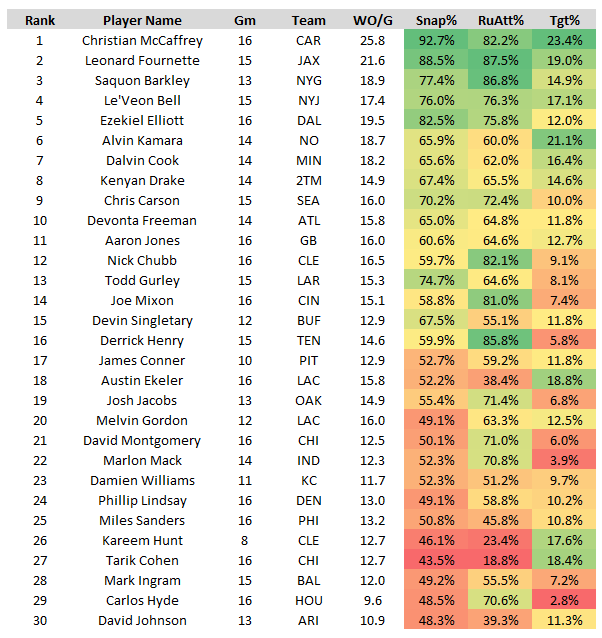

It’s rare for a team to feature only one running back with minimal relief. Christian McCaffrey was the only running back to play on over 90% of his team’s snaps last year, and only eight other running backs played on even two-thirds of their team’s snaps. A bell-cow running back is rare; it’s far more common for teams to feature multiple running backs in their offense. Whether that’s multiple running backs splitting snaps 60/40, 50/50, or 40/30/30, or one running back handling 70% of the rushing work and another handling 70% of the passing-down work, that’s a committee backfield.

A Handcuff

A backup running back playing on fewer than 30% of his team’s snaps in games active. In other words, they’re not viable for fantasy (even in DFS) unless the running back in front of them were to miss games.

Note: The term ‘handcuff’ was initially used to describe a backup running back you’re drafting in addition to the team’s starter, as a sort of insurance policy (in case the starter gets hurt). But even if you don’t own the starter, you can still draft a back-up running back as a means of capturing upside.

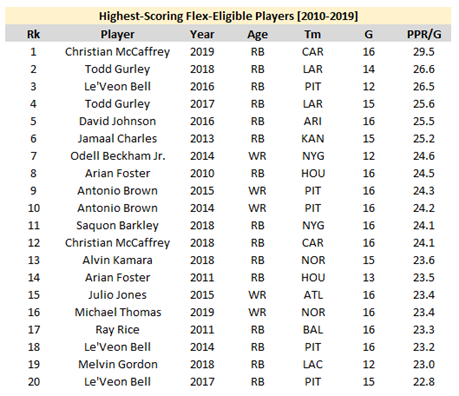

Bell Cow Running Backs – In-depth Explanation

As explained in Upside Wins Championships, it is not typically the well-rounded team with a starting lineup filled with good-but-not-truly-elite ADP-beaters that wins their league’s championship each year. Instead, it’s the team that drafted the correct one or more league-winning players. For instance, last season, teams that drafted Michael Thomas (the WR1), Chris Godwin (the WR2), and Derrick Henry (the RB3) were still less likely to win their leagues than teams that drafted just Christian McCaffrey. Power law distributions are a powerful thing. As I showed in Anatomy of a League-Winner, league-winners are typically running backs – it’s the most important position in fantasy. And the league’s top bell-cow running backs are typically the top league-winners.

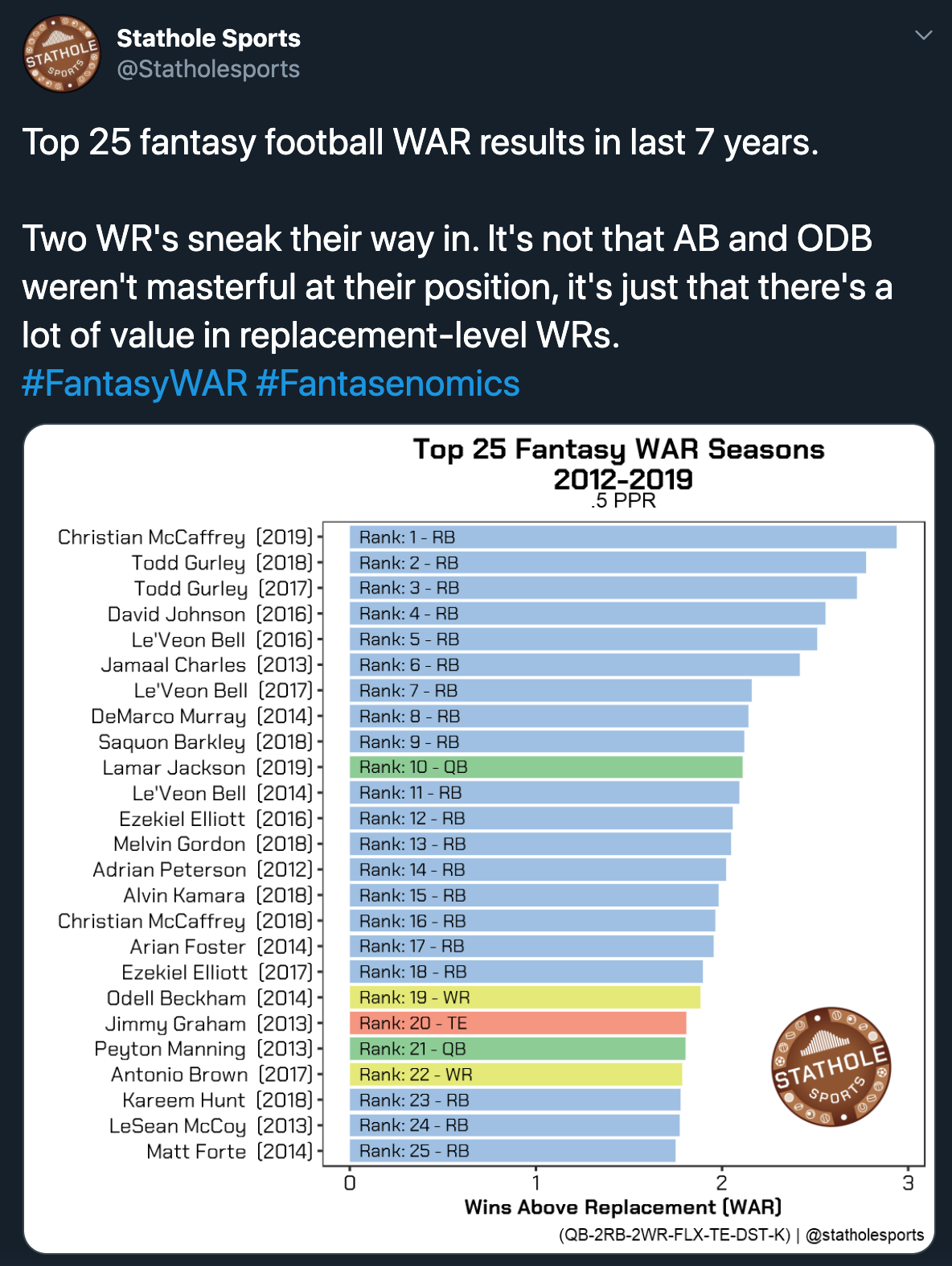

Consider the below chart which ranks the top-25 league-winning players (by WAR) since 2012.

Clearly, running back is the most valuable position in fantasy football, as running backs comprise 20 of the top-25 league-winners over the past seven seasons. And although a bell-cow running back is rare, it’s arguable that every running back on this chart was a bell cow in their league-winning season. All of the top-10 running backs earned a snap share over 75%, though typically only about 4.2 running backs per season would meet that threshold. And among all 20 running backs, only two earned a snap share below 70% – Melvin Gordon in 2018 (65%) and Alvin Kamara, 2018 (62%).

And even if a bell-cow running back is not a league-winner, even if everything goes wrong, they’re still likely to finish as an RB1.

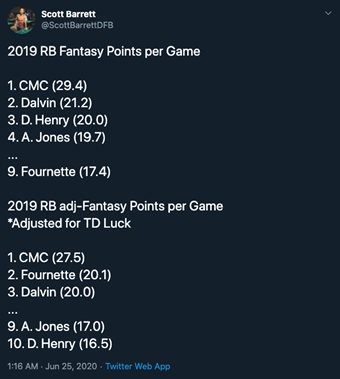

Consider Leonard Fournette. He saw brutal gamescripts all year – Jacksonville spent 72% of their offensive plays trailing (second-worst). He was on a bad offense (fourth-worst in points per game), playing behind a poor offensive line (seventh-worst, per PFF), and he was woefully inefficient, with unimaginably bad touchdown luck. By my data, only four other seasons this past decade were less efficient than Fournette’s 2019. Fournette ranked fifth in yards from scrimmage (1,674) and fourth in red zone opportunities (52), but 51st in touchdowns (3). If not for touchdown variance, and ignoring everything else just cited, he would have finished second at the position in fantasy points per game.

And in spite of all those headwinds, Fournette’s workload ensured he was still an every-week must-start, reaching at least 12.0 fantasy points in 14 of 15 games and averaging 17.4 per game (RB9).

Why? Because of volume. Because he was a bell-cow. Or, more specifically, because bell-cow running backs see the most volume, they receive the best types of volume, and their volume rarely fluctuates week-to-week.

Last season, Nick Boyle out-snapped Austin Hooper (769 to 724), but because Boyle was asked to block on 70% of his snaps (vs. just 29% for Hooper), Hooper ran over twice as many routes. Because tight ends can only score fantasy points when running routes, competent blockers can be at a disadvantage for fantasy. This means move tight ends (like Hooper) innately have a built-in advantage against in-line tight ends (like Boyle). For the most part, everyone already knows this (at least intuitively) and this is already factored into ADP.

Similarly, in most scoring systems, a 60-yard rushing touchdown is worth two 50-yard passing touchdowns. That’s a massive edge for someone like Lamar Jackson over Drew Brees. In general, mobile quarterbacks innately have a built-in advantage over pure pocket passers. This was an exploitable edge for a long time, but it seems this year ADP has finally adjusted.

Just like how mobile quarterbacks have an advantage over statuesque pocket passers, bell-cow running backs have a massive advantage over non-bell cow running backs. And unlike with quarterbacks this isn’t entirely captured by ADP, giving us a significant edge over our opponents.

For running backs, the two metrics that correlate best to fantasy points (well above any efficiency metric) are weighted opportunity points and snaps. Last season, McCaffrey averaged 64.9 snaps per game (most by any running back this past decade) and 29.5 weighted opportunity points per game (most by any running back this past decade). For Joe Mixon, those numbers were at 40.8 and 15.1, respectively. In other words, on opportunity alone, it was basically as if McCaffrey was playing six quarters per game to Mixon’s four. That’s a massive advantage.

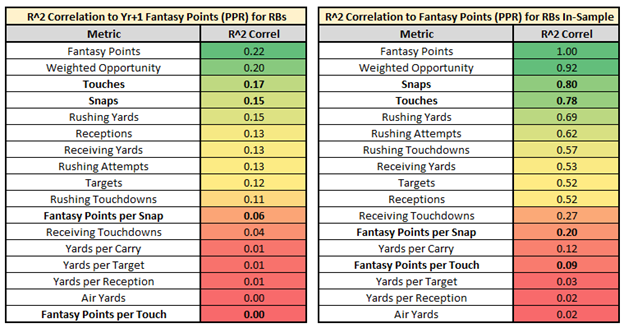

And it’s especially important because running back is the most volume-dependent position in fantasy. More so than for any other position, volume is so much more sticky, predictive, and valuable for running backs than efficiency.

As a result, bell-cow running backs out-score most other positions.

And bell-cows don’t just outscore other positions, they provide a huge advantage over their in-position peers, which then gives them an even greater advantage over the other positions. For instance, McCaffrey out-scored the next-closest wide receiver by +6.0 fantasy points per game, but he also out-scored the worst starter-worthy running back (RB24) by +17.5 fantasy points per game. That ranked well above Michael Thomas (+8.9), Lamar Jackson (+10.0), and Travis Kelce (+5.2). Of the top-nine players by this metric (VBD), seven were running backs. And this discrepancy becomes even more glaring when contrasting to the best available player on your waiver wire (rather than worst starter). Just look at the massive gap in Value Over Replacement for RBs compared to other positions:

Finally, bell-cow running backs also offer the least week-to-week variance in terms of both volume and production. That means they’re highly predictable and dependable week-to-week, which is incredibly important for start/sit leagues. Fantasy football is fundamentally a week-to-week game, and though a player may finish top-12, he won’t necessarily return top-12 value if the majority of his points came in a relatively few number of games and/or if he was more productive when on your bench rather than in your starting lineup.

Committee Running Backs – In-depth Explanation

Committee running backs rarely finish their season ranked among the bell cows. And it’s rare for two running backs on the same team to finish as starter-worthy players. In each of the past two seasons, there was only one instance of a team supporting two top-24 fantasy running backs. Two RB1s on the same team is almost unheard of, with the 2017 Saints being the only example in well over a decade.

The most common type of committee backfield is one where the rushing work is dominated by one running back (the early-down workhorse) and the passing-down work is handled by a different running back (the scatback or pass-catching back). One of the best recent examples of this is the 2018 Chicago Bears backfield of Jordan Howard (250 carries, 20 receptions) and Tarik Cohen (99 carries, 71 receptions).

While a bell-cow running back will be a lock-and-load every-week starter, a committee running back will be far more sensitive to game scripts. Teams lean more run-heavy when leading, which benefits the early down-workhorse. Teams lean more pass-heavy when playing from behind, which benefits the scatback. It’s no coincidence that over the past two seasons Derrick Henry, Aaron Jones, Josh Jacobs, and Joe Mixon all average at least 9.0 more fantasy points in victories than losses. Just like it’s no coincidence scatbacks like Tarik Cohen, Theo Riddick, Chris Thompson, and Nyheim Hines all average at least 2.5 more fantasy points in losses than victories.

Keep in mind, Henry (9.9 FPG), Jones (11.4 FPG), Jacobs (9.8 FPG), and Mixon (13.4) were almost all unstartable in losses. Marlon Mack is another terrific example, as the ultimate “get your exposure in DFS rather than season-long” running back. Over the past two seasons, Mack averaged 22.1 fantasy points per game in games Indianapolis won by 14 or more points. The rest of the time he averaged just 10.8 fantasy points per game. Essentially, you needed Indianapolis to win a blowout (which didn’t happen often), or Mack was actively hurting you if started in your lineup.

It’s rare for a committee running back to finish top-five, but not unheard of. Consider 2015 – an abysmal outlier year for the position – when Doug Martin (an early down workhorse) and Danny Woodhead (a scatback) both finished in the top-five. Although that surely seemed great, it’s doubtful either running back came close to returning top-five value. Both running backs were maddening to own for fantasy and rarely started in their best weeks, instead exploding on your bench. Woodhead finished outside of the top-24 running backs in 44 percent of his games, Martin in 38 percent. That meant either running back was only startable in (roughly) 60% of their games, despite finishing top-five.

Consider, this year, a running back like Tarik Cohen. I’d bet $50 he beats his ADP. But I’d bet another $50 he returns a win rate below 8.3% (or, worse than random in a 12-team league). He’s a great draft pick in a best ball league, but in a typical start/sit league, he’ll have the same problem most other committee backs have.

Over the past two seasons, Cohen has scored 16.0 or more fantasy points in 25% of his games. He’s also been held under 10.0 fantasy points in 44% of his games. Those down-games might not hurt you in a best ball league, where a computer automatically starts him in his best games and sits him in his worst games, but we won’t have that luxury in a start/sit league.

And, beyond that, if Upside Wins Championships, what’s his upside? At 181-pounds, I suspect Cohen is never going to be given a bell-cow workload. Instead, even if David Montgomery suffers an injury, he’d remain in that scatback role, capped at somewhere around 100 carries and 100 targets. He has virtually no chance at a top-seven season, and anything above a mid-range RB2 outcome still feels improbable. It’s not impossible, but like with Danny Woodhead in 2015 he’d need just about everything to break his way – he’d need to be hyper-efficient, he’d need ideal gamescripts (for Chicago to go 4-12 or worse), and he’d need Montgomery to struggle. And even then, he’d probably still be highly-volatile and frustratingly difficult to predict on a week-to-week basis.

It's more common for an early-down workhorse (rather than a scatback) to finish as an RB1, but it’s still hard to predict ex-ante. You need just about everything to break your way. As with Derrick Henry last year, you’d need both ideal gamescripts and unsustainably-great efficiency numbers. Correctly predicting gamescripts is difficult, but crucial. McCaffrey scored 29.5 fantasy points per game on a five-win team, but Henry might not have hit double-digit fantasy points. Even more difficult to predict, but just as crucial, is hyper-efficiency. Henry finished as a top-five running back last year, but he required the third-most-efficient running back season of the past decade to do it. Henry is terrific, but he was also unsustainably great – a true outlier. A season like that is rare, not to be relied on, and due for a massive regression. All of this is explained in more detail here and here.

This is the most common type of committee situation, but there are others as well. For instance:

- From 2016-2017, Devonta Freeman and Tevin Coleman shared a backfield where both rushing and receiving work was split 60/40 in Freeman’s favor.

- In 2011, for the Bears, Matt Forte received the majority of the work out of the backfield, but Marion Barber handled nearly all of the short-yardage and goal-line work.

- This year, it seems possible we may see multiple three-way committee backfields. For instance, Indianapolis could split rushing work between Marlon Mack and Jonathan Taylor (at least to start the year), while Nyheim Hines is handed the passing down work. That could also be the case in San Francisco with Raheem Mostert and Tevin Coleman splitting rushing work while Jerick McKinnon receives the bulk of the targets out of the backfield.

- Alexander Mattison was part handcuff and part relief pitcher last season, totaling 48% of his rushing yards in the fourth quarter, while Dalvin Cook remained on the bench basking in the glow of an inevitable blowout victory.

Handcuff (In-depth Explanation)

The James Whites and Tarik Cohens of the world are far less viable week-to-week than most people think. Yes, they’re volatile and difficult to predict. But, more importantly, they lack upside. And, as explained in Upside Wins Championships, mid-range RB2 production isn’t very valuable at all. The difference between starting the RB20 and the RB36 (2.6 FPG) is nothing compared to the difference between starting the RB7 and the RB20 each week (5.7 FPG).

But the problem with handcuffs is that they’re (by definition) wholly useless week-to-week unless the starter in front of them gets hurt. That’s rare – rarer than most people think – and impossible to predict.

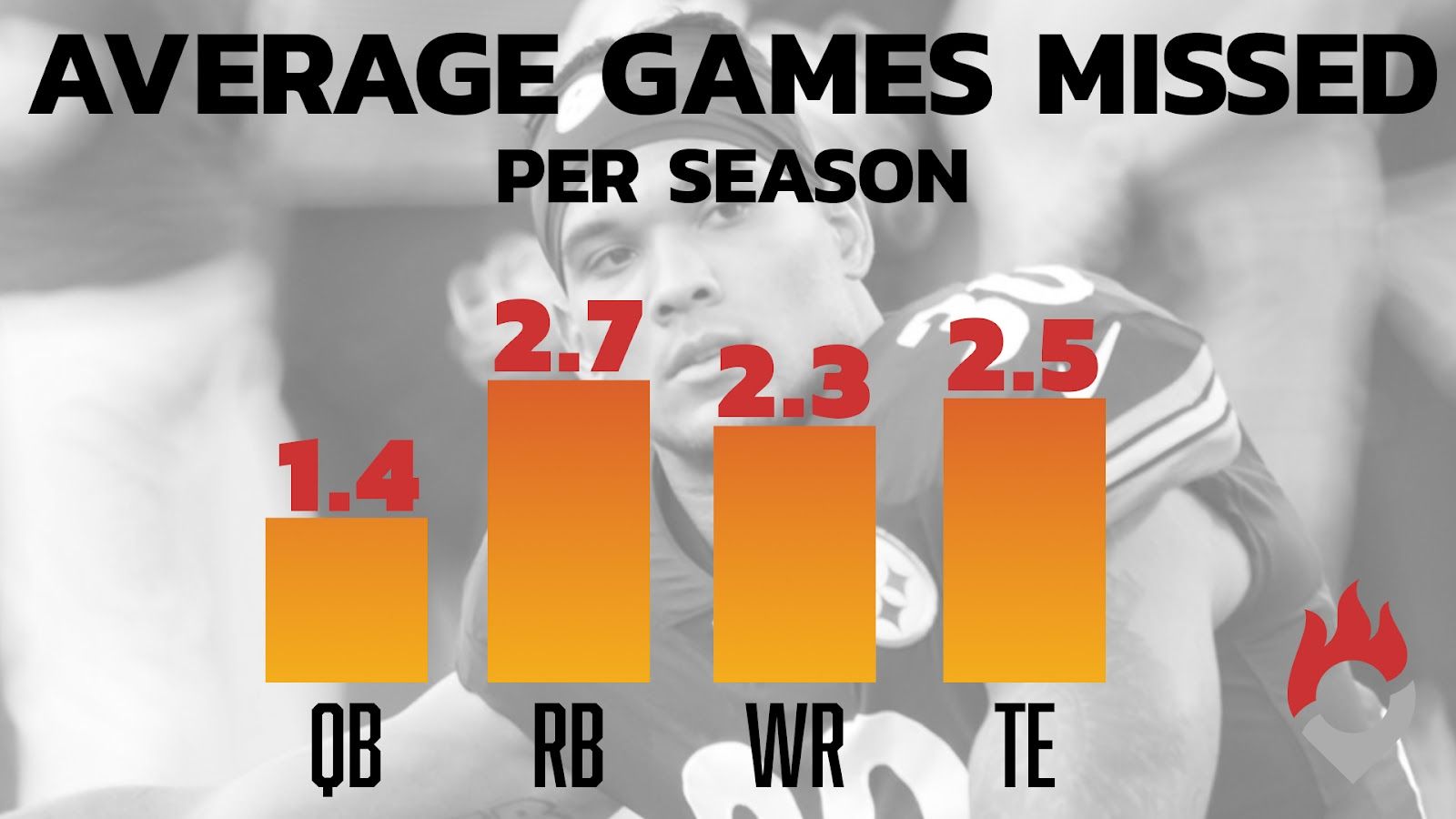

Looking back at all players drafted in the first 10 rounds (by ADP) over the past 10 seasons and only looking at games lost due to injury (scrubbing out suspensions or games inactive due to performance), it’s clear that (contrary to popular opinion) running backs aren’t significantly more injury-prone than wide receivers and tight ends.

Granted, I like these players, because I do think they have RB1 upside should their starter go down (and that’s rare and valuable), but drafting a handcuff is like buying a scratch-off lottery ticket. You know going in it’s -EV. I’ll draft Murray because of his bell-cow potential (should Kamara suffer an injury), but I’m not counting on it.

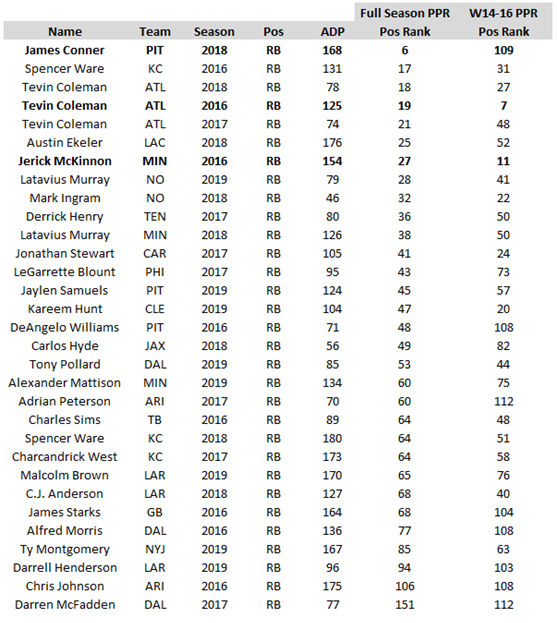

Over the past four seasons, James Conner (2018) was the only handcuff to finish a season top-15 in fantasy points. Tevin Coleman (2016) and Jerick McKinnon (2016) were the only running backs to finish top-15 in fantasy points during the postseason weeks (Weeks 14-16). Of 31 qualifiers, this would put the hit rate somewhere between 3%-6%.

For this exercise, “handcuff” was defined as a running back who had an ADP in the top-200 who was also drafted after a teammate who ranked top-12 at the position by ADP. (As we alluded to earlier, Coleman probably shouldn’t have been counted as a handcuff.)

Of course, there were a few instances where a handcuff went off in the middle of the season for a few games before the starter returned (Latavius Murray, 2019), but what’s that worth in terms of leading you to a championship? Not much!

Strategy

ADP hasn’t yet fully recognized the inherent advantage of a bell-cow running back, but that doesn’t mean bell cows come cheap. As we showed in Anatomy of a League-Winner, over the past four years 47% of the top league-winning running backs were drafted in the first four rounds. That’s partly a function of ADP accuracy, partly a function of running backs being more valuable than all other positions, and partly a function of just how valuable high-end running back production is. By that last point, I just mean that it doesn’t really matter where you drafted a running back so long as they returned high-end production.

Value matters, but it doesn’t seem to matter anywhere near as much with running backs as the other positions. Again, you need high-end producers, it doesn’t really matter where you get them, but they’re typically only found early in drafts. On that point, imagine I have a running back ranked 10th overall who is being drafted in Round 2, as the 12th-overall running back. And I have another running back ranked 18th being drafted in Round 5, as the 28th-overall running back. It’s not obvious to me that I’d be better off drafting the latter running back in Round 5 than the former running back in Round 2, although that’s almost certainly the case for the other positions.

ADP is pretty good, but it’s far from perfect, and still very exploitable. ADP always overrates mid-range committee backs without much bell-cow potential while underrating handcuffs with bell-cow potential. To me, a pure handcuff like Tony Pollard should have a higher ADP than a pure committee back like Sony Michel, Marlon Mack, or Duke Johnson. (Although none of these players will be serious targets.) ADP also massively overrates committee backs coming off of big years (Aaron Jones, Derick Henry, Nick Chubb), and this will be one of our biggest edges – avoiding the high-priced landmines at the top of your draft. And, as we’ll show tomorrow, ADP can also overlook a few obvious bell cows. So, what am I doing in drafts?

I’m going “Bell-Cow or Bust.” I’m only ever drafting bell-cow running backs or committee backs/handcuffs that I think can become bell-cow running backs.

For instance, if I think J.K. Dobbins is going to be stuck in a committee with Mark Ingram, I’ll be avoiding him at APD (RB30). If I’m drafting him, it’s because I think – at least by some point in the season – he’ll supplant Ingram and become the featured running back in the offense, only occasionally spelled by Ingram or someone else. The more likely this is, the more I would make him a target.

Dobbins might supplant Ingram based on talent alone, but – like with handcuffs – committee backs also have injury-upside. If Ingram were to miss time due to injury, it’s likely Dobbins would be gifted a bell-cow workload until he returned. While that should be factored into his upside, again, good luck predicting that. Although it would be more valuable if he supplanted Ingram (on talent) in Week 1, that’s highly unlikely. If it were to occur, it wouldn’t be until halfway through the season or later. But, because playoff weeks matter more, that would still make him far more valuable than a true committee back.

For instance, rookie season David Johnson was an all-time league-winner even though he was only startable in three or four games all year. He was in a three-way committee for much of the season, before being granted a bell-cow workload in Week 13. From that point on, until Week 16 (Championship week), he averaged 26.0 fantasy points per game on 23.3 touches per game. Before that, he averaged just 9.4 fantasy points per game on 4.9 touches per game.

Derrick Henry (RB6 by ADP), who is unlikely to catch even 20 passes this season, or Nick Chubb (RB9), who is guaranteed to remain in a committee alongside Kareem Hunt, are two players I’m outright fading. They’re committee backs priced like bell cows. Of course, if they had an ADP in Round 7 (instead of Round 1), they’d be must-draft targets. So, there are exceptions.

But, for the most part, each time an opponent drafts a low-upside committee-back without bell-cow potential (e.g. Mark Ingram, Devin Singletary), I’m grinning, because that’s an extra high-value or high-upside pick leftover for me.

Get to the point already!

To summarize, bell-cow running backs are for a number of reasons (volume, consistency, predictability) inherently more valuable than non-bell cows. That’s not always or not entirely reflected in ADP, which then represents an edge to us. Okay, so what does a “Bell-Cow or Bust” strategy look like in practice? It’s going to look different each season, but in 2020 drafts I’m almost always drafting a running back in Round 1 and then another running back in Round 2 or Round 3. I’ll almost always have three running backs (no more, no less) by the end of Round 6 (I currently have two favorites being drafted at the Round 5/6 turn). And then if I draft another running back (and I might not), it would only be one or two running backs very late (usually a handcuff-type).

So, which players are going to be bell cows in 2020? Who are you targeting in drafts?

I’ll answer these questions tomorrow. (Sorry!)

Well then, who were the bell-cow running backs in 2019?

At the highest end of the spectrum, we’re talking about the Christian McCaffrey, Saquon Barkley, and Ezekiel Elliotts of the world, though last year Leonard Fournette and Le’Veon Bell also would have qualified. They were rare outliers in an oddly outlier-ish and genuinely weird year for bell-cow running backs.

I’ve defined “bell cow running backs” far more narrowly in the past, such as running backs that receive at least 66% of their team’s backfield snaps, carries, and targets in games active. Though convenient, I think this tends to obscure the message. Instead, we should be looking at things on a spectrum.

Was McCaffrey a bell cow last season? Yes. Was Derrick Henry? No. Was Chris Carson? Maybe. At the very least, he was certainly less of a bell cow than McCaffrey and far more of a bell cow than Henry.

Here are all running backs last season, by a weighted average that incorporates Snap%, Rushing Attempt%, and Team Target% in games active:

This chart (taking an average of Snap%, Carry%, Target%) serves as a general ranking of how much of a “bell cow” each running back was.