In this day and age, it is rare to actually find a new, never-before-used stat that is both useful and predictive for fantasy football. Thanks to the thousands of hours of charting and development poured into the Fantasy Points Data Suite, today I will present a stat fitting exactly that description – first reads.

What is a first read? We define it as the first set of options the QB checks after taking the snap. That could mean a single receiver’s route, such as a designed screen, or it could be multiple receivers running routes on one side of the field. If the QB throws somewhere within this original window of opportunity, he is credited with a first-read throw, while the targeted receiver is credited with a first-read target.

Yes, this means multiple players (for example, the slot and the wideout) are often simultaneously running routes within the QB’s first read. But if the QB ultimately throws to the slot, only that receiver is credited with the first read. Why? On any given play, the targeted receiver is the only one whose read assignment can be determined with a reasonable degree of certainty. Unless teams start releasing their entire playbooks, this is likely the best we can do.

Of course, that won’t stop me and the Fantasy Points Data Suite from providing actionable takeaways for your 2023 fantasy drafts. One note before we begin: the Data Suite allows you to separately filter between first reads and designed throws (destined for only one receiver, such as a screen). However, since they both indicate the team’s intention on the play, I’ll generally combine the two and analyze them together for the entirety of this article.

Importance of First Reads

How big of a deal are first reads? Consider these broad stats from over the past two seasons:

Teams threw to the first read on 67% of their pass attempts on average over the past two years.

88% of targets to WRs and TEs came on a designed play or a first read.

Passers averaged 7.9 YPA on first reads, and just 6.9 YPA on all other throws. That’s a full yard more if the offense can execute “Plan A.”

5.1% of first-read throws result in touchdowns, compared to just 3.5% of all other throws. In other words, first reads result in scoring 45% more often.

First reads represent the offense’s original intention, so it’s no wonder they are both significantly more efficient and more frequent than other reads. We even see a slight difference in target accuracy – in 2022, 80.6% of targets coming on the first read were deemed catchable. Of all other targets, just 76.9% were catchable. QBs and play-callers alike would prefer to stick to the first read as much as possible.

Naturally following from the above, the vast majority of fantasy points are scored on first reads. In fact, they’re practically all that matter. To illustrate, here are the top-10 WRs from 2022 by receiving yards, if you removed all first reads and designed targets:

Pay particular attention to the minuscule target and yardage totals. In this bizarro world, JuJu Smith-Schuster would have led all WRs with a whopping 4.2 FPG. Justin Jefferson would have finished as just the WR31.

As should now be apparent, it is relatively rare for a receiver to be targeted if they were not on the first read of the play. That means that behind most targets is some amount of intention on the team’s part. That doesn’t mean you should stop believing targets are “earned” (because they are, and because multiple players can be running a route and competing for the target within the QB’s first read). But on some level, targets must be earned on the whiteboard before they can be earned on the field.

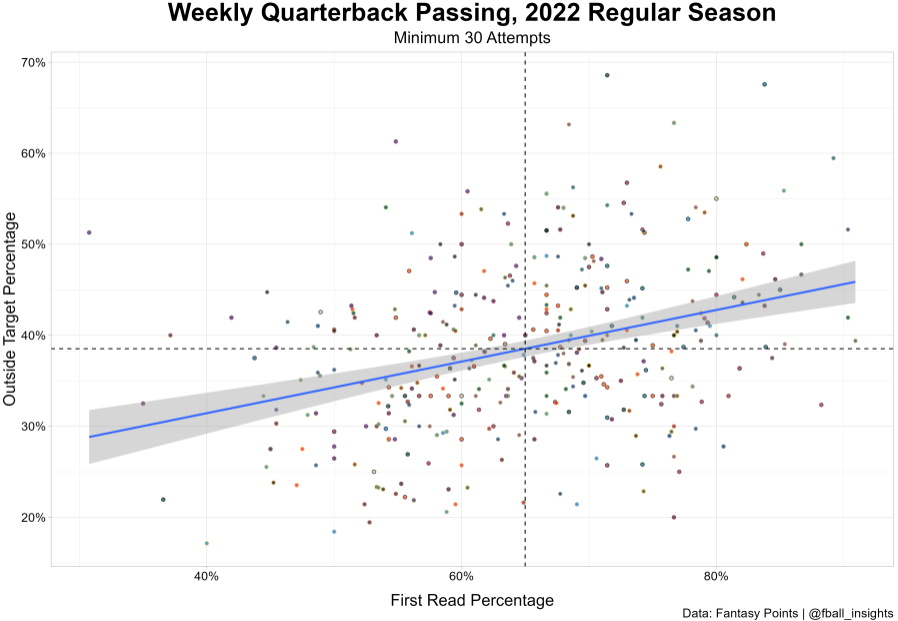

Some offenses manage to utilize first reads more often than others. What can that tell us? As it turns out, quite a lot. When QBs can execute the first read more often, it means they are throwing with greater frequency to players lined up on the outside:

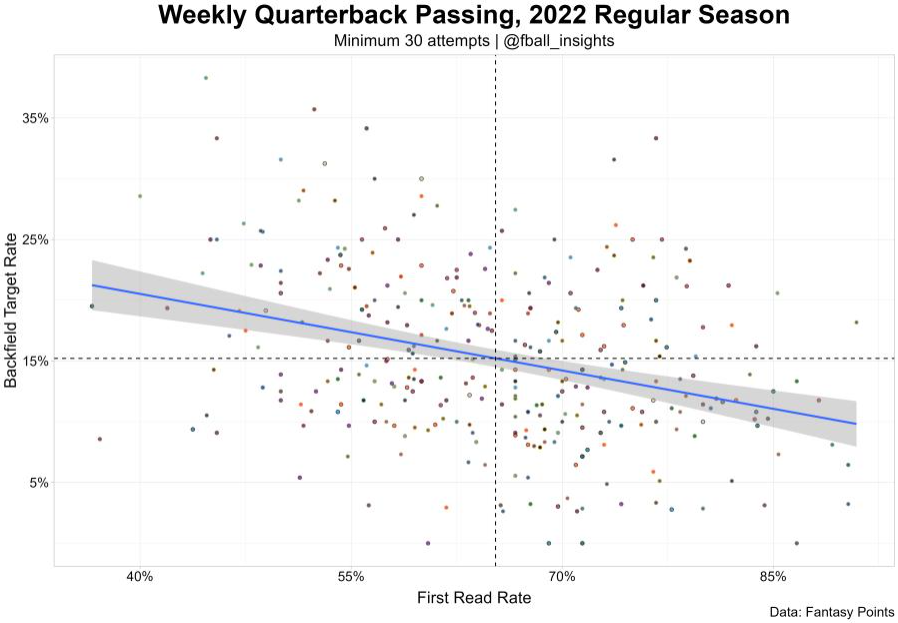

Conversely, first read-heavy offenses throw to players lined up in the backfield relatively less.

The why seems fairly intuitive – teams generally look to throw to receivers first, and if that fails, the QB can check down to the running back. The more interesting question is why teams do or do not conduct first reads at a high rate in the first place – because that could give us hints about which teams may target their WRs or their RBs more or less frequently, critical information for fantasy football enthusiasts.

Quarterbacks and First Reads

It is tempting to say that certain QBs are simply better than others at progressing through all of their reads when needed. After all, don’t rookie QBs find it notoriously difficult to make it past the first read? It’s harder to make that case than one might expect. Trevor Lawrence, Zach Wilson, Kenny Pickett, and Skylar Thompson all ranked below average in first-read throw rate as rookies. While some QBs ranking high in first-read throw rate over the past two seasons (like P.J. Walker and Drew Lock) are likely there due to genuine deficiencies, the top of the list is also littered with highly effective passers such as Tom Brady and Matthew Stafford in 2021, or Lawrence in 2022.

If first reads alone were a sign of struggling passers, we would expect QBs ranking highly in it to fare poorly in other metrics. In reality, first-read throw rate has virtually no correlation to fantasy points per dropback (-0.02) and only a slight negative relationship with a metric like CPOE (-0.10). So perhaps QBs might rank high in first read throw rate if they either have trouble processing quickly or can competently pilot a well-schemed offense, like in the cases of Brady, Lawrence, and Stafford?

A significant issue with this dual hypothesis is that first-read rates are not very sticky for QBs – the metric has just a 0.14 correlation to itself the year afterward. Even worse, on the team level, the year-to-year stickiness is near-zero. Why would this be the case? A few QBs like Lawrence and Russell Wilson had new play-callers in 2022, which could partially explain the wild swings they experienced in first read rate. But what about the rest?

Lawrence went from a below-average (66.1%) first-read throw rate in 2021 to one of the highest in the league (75.0%) in 2022. Jalen Hurts similarly progressed from a rather low 65.7% (10th-lowest) in 2021 to a well-above-average 71.4% rate last season. On the other side of the coin, Justin Herbert’s 71.0% first read throw rate (8th-highest) in 2021 free fell to just 57.1% (2nd-lowest). Russell Wilson saw the second-largest decline among fantasy-relevant passers, from 68.0% to 55.7%.

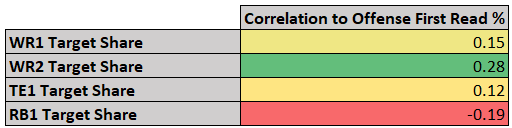

What commonalities can we find between the above four QBs – who saw the most extreme first read throw rate changes in each direction? While only Lawrence and Wilson had new play-callers, all four experienced significant changes in receiver quality. Between them, Hurts and Lawrence received A.J. Brown, an improved DeVonta Smith, Christian Kirk, Evan Engram, and Zay Jones. Conversely, Herbert dealt with injuries to Keenan Allen and Mike Williams for much of the season, and Wilson downgraded from D.K. Metcalf and Tyler Lockett to Courtland Sutton and a somewhat banged-up Jerry Jeudy. Perhaps receivers – not quarterbacks or offensive coordinators – primarily determine how often the QB can throw to their first read. This becomes more convincing when we notice that the alignment (outside vs. backfield) trends from earlier are also borne out at the player level:

If target share can be taken as an approximation of player skill, we might flip the assumed causal chain from earlier. Maybe it is not that certain QBs and schemes lead to first reads, which funnel targets to WRs and away from RBs. Instead, perhaps good receivers allow teams to throw on the first read more often – because good receivers get open when they’re on the first read. The team’s WR2 (measured by target share) having the strongest relationship to overall first read throw rate buoys this argument – being able to have two competent WRs working on the first read (which, remember, is more often an area of the field than a single player’s route) makes it much more likely one will get open.

Now, the above correlations are admittedly not massive, and they don’t blow away the year-to-year QB correlation. The real answer is likely that all three factors of QB tendency, scheme, and receiving personnel have conflicting effects on first-read throw rate. But the examples of Lawrence, Hurts, Herbert, and Wilson are instructive for fantasy football. Remembering the significant efficiency gains associated with first-read throws, we likely underrate the impact that gaining or losing weapons has on QBs from a fantasy perspective.

Imagining first-read throw rate as receiver-determined might encourage us to project a significant leap forward for Justin Fields, who is adding D.J. Moore to his arsenal after posting a slightly below-average 66.7% first-read throw rate in 2022. Even if more open looks lead to fewer scrambles, Fields becoming more efficient as a passer would enable him to reach game-breaking heights. It’s no coincidence that the two QBs ranking directly above him and the one directly below him in designed rush attempts last year are responsible for three of the past four QB1 overall seasons by FPG.

QB designed rush attempts per game, 2022:

— Ryan Heath (@QBLRyan) July 6, 2023

1. Jalen Hurts: 8.1

2. Lamar Jackson: 7.2

3. Justin Fields: 6.3

4. Josh Allen: 4.6

5. Marcus Mariota: 4.5

6. Daniel Jones: 4.1

7. Kyler Murray: 3.8

Via @FantasyPtsData

We might also envision a bounce-back season for Justin Herbert, who, as previously mentioned, fell from an above-average first-read throw rate to near the bottom of the league last season. Due to injuries, there were only three games in which both Keenan Allen and Mike Williams ran over an 80% route share. In those three games, Herbert’s first read throw rate improved to 59.4% – still well below average, but better than the 56.7% from Herbert’s other games. With healthy weapons and a shiny new toy in Round 1 WR Quentin Johnston, new OC Kellen Moore should have no trouble scheming a more workable offense – Dak Prescott displayed a 68% first-read throw rate under Moore last season. And good ol’ positive regression in terms of red zone scoring ought to help Herbert a ton as well. Last year he scored on only 18% of his red zone opportunities, the 5th-lowest rate in the league.

Which QBs scored the most TDs on their red zone opportunities?

— Ryan Heath (@QBLRyan) June 29, 2023

- Top-6 in well-schemed offenses (McDaniel, Moore, Shanahan, Smith, Reid, Daboll)

- Justin Herbert screams positive regression — especially with Kellen Moore on the way

- Hurts can be even better than you thought pic.twitter.com/JagLf1mILO

Among QBs with 200+ dropbacks, Deshaun Watson had a bottom-6 first-read throw rate, while teammate Jacoby Brissett ranked a more respectable 18th. Being thrust into a new offense mid-season could absolutely have contributed to Watson’s struggles, a problem that should be remedied with a full offseason of work. Adding Elijah Moore (who led the Jets in first-read target share as a rookie in 2021) also can’t hurt.

Ryan Tannehill now gets to throw to DeAndre Hopkins, whose 33.5% first-read target share ranked top-10 in 2022. Last year, no Titans receiver commanded greater than a 20.8% first-read share. That was the lowest mark by any team’s leader, while the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and Green Bay Packers were the only other teams not to have any player reach 25%. Tannehill has had no target dominator since the departure of A.J. Brown.

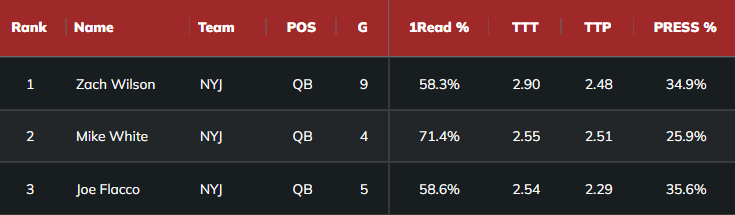

Finally, the 2022 New York Jets (who were unique in that they had three passers with over 150 dropbacks) unlock the final – and possibly the most important – piece of the puzzle. Despite playing under the exact same play-caller and throwing to the exact same weapons, Mike White’s 71.4% first-read throw rate ranked 4th, while Joe Flacco’s and Zach Wilson’s 58.6% and 58.3% marks were both bottom-five. So what gives?

We can see that White was pressured on only 25.9% of his dropbacks (4th-fewest), while Flacco and Wilson were each pressured about 35% of the time (8th- and 11th-most). In Wilson’s case, it was probably because he held the ball for too long – his 2.90-second average time to throw (TTT, visible) ranked 3rd-slowest. This could indicate Wilson failed to execute on the first read, resulting in more frequent pressure.

Flacco may have simply been unlucky – his 2.29-second average time to pressure (TTP, also visible) was the sixth-fastest. Reversing the causation again, this suggests that quick pressure from poor pass protection often knocked Flacco off the first read, leading him to check down to the safety valve at a 14.1% rate, the highest in the NFL.

For mobile QBs, pressure might instead induce scramble drills, another result that is not a first read. Each of the top-4 scramblers in 2022 ranked below average in first read rate.

Whether caused by time to pressure or time to throw (or their causal relationship together), our intuition that pressure rate and first read throw rate are connected proves correct – the correlation between the two metrics for QBs with 50+ dropbacks was -0.36. In other words, QBs who are pressured often throw to the first read relatively less, while QBs who rarely face pressure throw to the first read relatively more. Remembering that first reads average a full yard per attempt more than other pass attempts reveals the critical importance of pass protection to NFL offenses – even when the QB is merely pressured and not actually sacked.

Pass Catchers and First Reads

While the first read puzzle at QB is quite complicated, the picture becomes much clearer for WRs and TEs. At those positions, the metric becomes highly sticky and highly predictive. First-read target share sports a 0.78 correlation to itself the following year, as well as a 0.79 correlation with next-season FPG (PPR scoring).

Though first-read target share functions similarly to regular old target share (both in statistical predictiveness and in application), it does have a few advantages. For example, the top 20 WRs/TEs by target share scored 15.7 FPG in 2022. The top 20 by first-read target share scored 16.2 FPG.

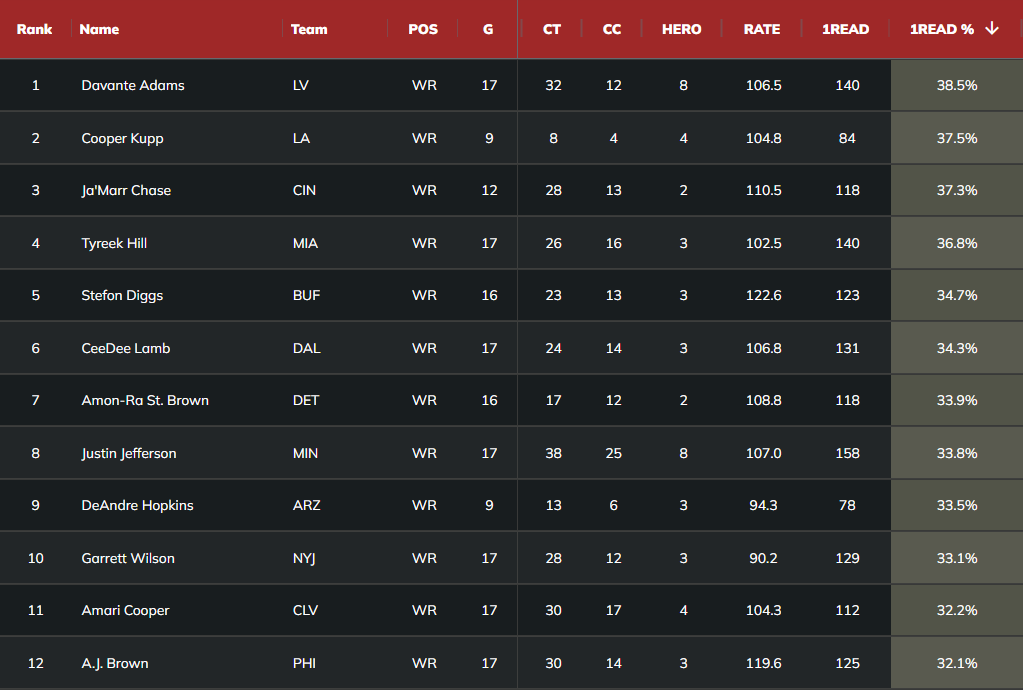

In fact, gaze upon the top-12 WRs by first-read target share for your viewing pleasure. You’re looking at the most alpha of the alphas – not just in terms of actual targets, but in terms of how often their teams intended to target them.

First-read target share (player first-read targets divided by total team first-read targets) is one step earlier in the causal chain of how players score fantasy points. Since most targets come on the first read, play-callers must design and select plays with a receiver on that specific assignment before the receiver can be targeted. The metric also allows us to compare how receivers perform at earning targets on first reads (again, the most frequent, important, and efficient types of plays) to how they perform at earning targets overall.

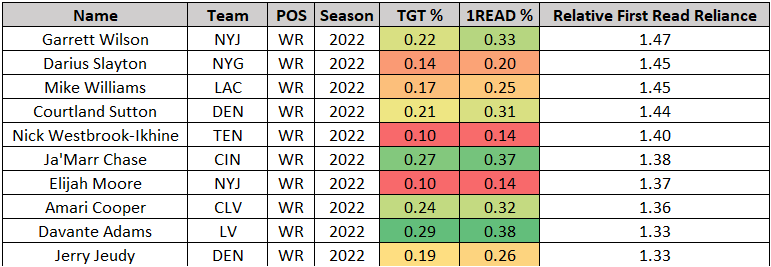

On that last point, comparing first read share to regular old target share provides insight into which players’ fantasy fortunes most hinge on how often their teams decide to draw up plays for them. Players with relatively higher first read shares than overall target shares performed much more effectively on the first read than otherwise – because a player must still get open to receive a target, even if they are on the first read.

Since most targets happen on first reads (and first reads are more efficient), these players can be incredible assets both in real life and in fantasy football. But that also means those players are much more reliant on first reads – if their team sours on them and decides to stop designing plays for them as often, they are left with only their comparatively worse ability to earn targets on non-first reads.

As you may have guessed, the NFL’s most first-read-reliant players are largely outside WRs who win with some level of physicality. If their teams are committed to funneling them opportunities (Ja’Marr Chase, Davante Adams, and Garrett Wilson), they can be highly effective target hogs. But if the team loses faith in the player (as we’ve seen happen to Darius Slayton, Courtland Sutton, and Elijah Moore at different points in their careers) their utility instantly vanishes as they morph into the rarely-used decoy X archetype. Theoretically, this could work in the other direction as well – if their new coaching staffs see great value in Moore or Jerry Jeudy, they could quickly become hyper-productive players.

Moore, in particular, has a compelling upside case. As a rookie, he immediately proved he could win both inside (as he did in college) and outside, his 1.95 YPRR from out wide ranking 23rd overall and 3rd among rookies, behind only Ja’Marr Chase and Jaylen Waddle (min. 200 routes). Aside from fewer games played, Moore’s rookie campaign as a whole was quite similar to Amon Ra St. Brown’s and DeVonta Smith’s, with the trio rightfully viewed as similar bets entering 2022. The latter two ended up smashing as mid-round picks, finishing as the WR10 and WR13 in FPG, respectively.

Plotting rookie WRs by FIRST READ TARGET SHARE — the percentage of the team’s throws on a first read that went to the player

— Ryan Heath (@QBLRyan) July 19, 2023

Compared to regular target share, this gives us more of a window into who the team intended to throw the ball to.

All per the charters @FantasyPtsData pic.twitter.com/oTUUcz0R1S

In contrast, Moore’s sophomore season was an abject disaster. Though his 72.3% route share ranked second on the team to only Garrett Wilson, Wilson was targeted on the first read 2.5x more often than Moore. Even when the QB did look Moore’s way, only 70.5% of his targets were catchable, the 6th-lowest rate among all WRs (min. 200 routes). On the occasions Moore did get the ball, he was electric – ranking 2nd with 0.32 missed tackles forced per reception behind only Deebo Samuel. If considering only first and designed reads, Moore’s yards per target was 7.96 – virtually identical to Wilson’s 7.89. The Jets simply weren’t involving Moore in the areas he excels.

Though Moore must now compete with Amari Cooper, we should not underestimate the role that simply being liked by a coaching staff plays in consolidating first-read opportunities. It’s easy to read between the lines that Moore and the Jets did not see eye-to-eye, culminating in a dramatic mid-season trade request and public statements about wanting the ball more. In stark contrast, Browns HC Kevin Stefanski has showered Moore with praise, gushing, “He takes it very seriously. Which is great. It’s fun to be around a guy that really works at it. He’s taken the bit on everything we’ve asked him to do.”

#Browns Kevin Stefanski on WR Elijah Moore pic.twitter.com/Pt2XJTR0J9

— Mary Kay Cabot (@MaryKayCabot) July 24, 2023

Maybe Moore’s rookie numbers were simply a result of lackluster target competition within a relatively small sample of games, and he is truly no more than a complementary player in the NFL. Or maybe he’s a future star who was held back by a personality conflict. Now that he’s in a new home where he’s apparently a culture fit, why wouldn’t you want to find out whether he’ll be fed first reads once again at his WR44 ADP?

To finish with some quicker hits, I’ve discussed Jerry Jeudy’s upside in a Sean Payton-led offense already this offseason, but I’ve so far been dismissive of Courtland Sutton. And perhaps rightfully so – his 1.56 YPRR over the past two years pales in comparison to Jeudy’s 2.12, and Sutton has never really been the same since tearing his ACL and MCL at the start of the 2020 season.

Still, even with the efficiency gap, Sutton’s 50.2 YPG average over the past two years is fairly comparable to Jeudy’s 57.6 thanks to Sutton running significantly more routes – about 5.2 more per game last year. Despite similar overall target shares, that preference for Sutton over Jeudy also shined through in first reads – Sutton led the team in them during 11 of his 15 games last year, tying him with Amari Cooper, Chris Olave, and DK Metcalf for the 4th-most in the NFL.

The new coaching regime could scale back Sutton’s opportunities (and thus his first reads), but if he holds on to his role, he is a candidate for positive touchdown regression. Sutton’s 14 end zone targets were tied for the 5th-most among all WRs, but he scored on just 14% of those opportunities – the 4th-lowest rate among WRs with 5+ end zone targets.

Plotting end zone targets against TD rate on those targets via @FantasyPtsData reveals both usage trends and regression* candidates

— Ryan Heath (@QBLRyan) July 24, 2023

- Lamb, ARSB, Waddle were relatively lucky on few EZ targets

- Metcalf, Wilson, Diontae, and Jefferson (somehow) could score much more this year pic.twitter.com/JXiMTWaijy

While end-zone targets are sticky, end-zone scoring rate is not – suggesting Sutton could capitalize on one of the more robust end-zone roles in the NFL with slightly better luck this year. This won’t make me start drafting him heavily, but maybe I’ll stop skimming over his name entirely when I desperately need to shore up my WR depth at the 8/9 turn on Underdog.

Darius Slayton’s 20.3% first-read target share was enough to lead all Giants receivers last year (aside from Sterling Shepard, who played only three games). He’s also a more explosive playmaker than he often gets credit for, ranking 6th among all WRs/TEs in depth-adjusted yards after catch per reception.

While the team has added a number of playmakers this offseason, nearly all of them are best suited for the slot, giving Slayton a clear path to starting on the outside. That’s a signal the coaching staff might be getting higher on him – after all, Slayton remarkably went from being a healthy scratch at the start of 2022 to re-signing with the team this offseason.

Like the rest of the WRs ranking high in first-read reliance, Slayton is incredibly productive as long as he’s getting the ball. During the 7 games in which he led the team in first read share, Slayton averaged a bonkers 51.5% air yards share, 2.62 YPRR, and a respectable 10.7 FPG by Underdog’s scoring – where he is being drafted in the 17th round as the WR84. I won’t pretend to be clued in on the matchup tendencies that drive the team to design the entire offense around Slayton in some games and ignore him entirely in others, but I do know this makes him an incredible late best-ball pick likely to make your lineup several times throughout the year.

While the preceding three WRs have not earned the amount of volume needed to be incredible fantasy producers as of late, we have reason to speculate their teams may be higher on them than they were at this time last year. Since they disproportionately benefit from first reads, they are theoretically the highest-impact players to make such a bet on.