To the typical redraft player, dynasty league managers appear overly obsessed with age. Your average dynasty junkie is more of an ageist than Leonardo DiCaprio. Seemingly, the exact second an RB turns 25 – regardless of who it is – their draft stock plummets by 4-8 rounds.

But are fantasy managers correct in their age-based discrimination? This question – and more generally, the impact of age on fantasy performance – is the focus of today’s article. Redraft players will likely find this analysis just as valuable as dynasty degenerates; age is also a critically important factor in spotting potential breakouts and ADP values.

In choosing where to focus our attention, we probably aren’t as interested in how mediocre players or one-hit-wonders like 2020 James Robinson (RB7) or 2019 Kenny Golladay (WR9) perform as they age. We’re instead curious at what ages annual high-end producers like Christian McCaffrey, Davante Adams, and Travis Kelce reach their primes and begin their demises.

To investigate, I looked at all players since 2000 across the totality of their career, excluding players who failed to finish top-12 at their position (by PPR scoring) multiple times. (For TEs, I used multiple top-6 finishes as our cut-off.) That left me with the sample upon which all of the following analysis is based.

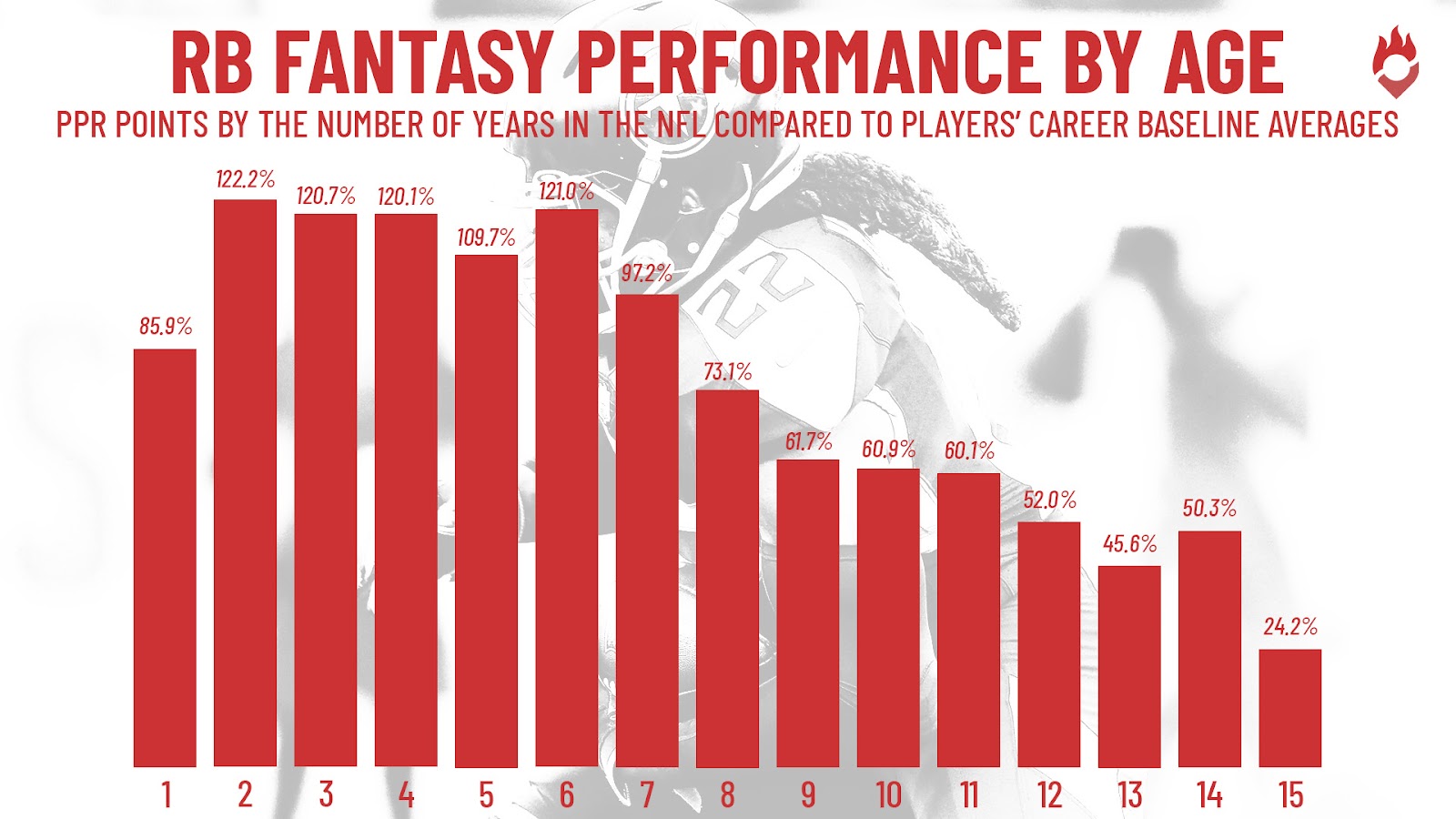

Within each position, I compared fantasy performance in each career year to the average baseline performance over an entire career. This resulted in the aging curves below.

Statistical Disclaimers (feel free to skip)

Before you attempt to interpret the curves, we must first understand their limitations. Adam Harstad’s evergreen piece on aging curves and mortality tables best explains why this style of analysis is prone to survivorship bias and the ecological fallacy.

As a concrete and 2023-relevant example, Ezekiel Elliott is entering the eighth year of his career. If he fails to find a job this offseason and scores zero fantasy points in 2023 as a result, he would not have any effect on our sample of Year 8 players, nor on Year 9, Year 10, and so on. This is survivorship bias – our curves cannot account for players who do not survive to that point in their careers. Therefore, consider every data point in this article to be preceded by the statement “among players who made it to that year of their career…”.

The ecological fallacy is a bit less intuitive. In short, an average of a group may or may not be a useful representation of any of the group’s individuals. When presenting the average of many data points, you will inevitably lose information about the individuals within the group. This is especially dangerous if the data is not normally distributed (shaped like a bell curve).

On that point, we should remember from Scott Barrett’s magnum opus (Upside Wins Championships) that fantasy football is a game ruled not by normal distributions, but by power law distributions. And power law players – the players who really determine our fantasy fates – will skew our data and should be treated distinctly from anything related to “average.” In short, we should always expect a Tom Brady, Tony Gonzalez, or Jerry Rice-like talent to age more gracefully than a merely “good-to-great” player.

Since you and I are now hyper-aware of these issues, I’ll be accounting for them in the analysis below.

Running Backs

Key Takeaway: Generally, RBs take a big step forward from Year 1 to Year 2. Years 2-6 are peak years, with that peak production largely remaining stagnant. Year 7 provides the first hint of a steep and precipitous decline toward irrelevancy. From Year 8 on, RBs are usually worse off than when they were rookies.

On average, the league’s best RBs experience a 42% increase in production from Year 1 to Year 2. However, I again caution that an average is not representative of any individual. For instance, Saquon Barkley and Ezekiel Elliott were uniquely hyper-productive as rookies but did not see anywhere near a 42% production boost in their follow-up season. The clear lesson is to target cost-controlled RBs entering Year 2 – those who have yet to peak and can outperform a subdued ADP.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can create compelling justifications for why RBs do not always break out immediately. Most commonly, a highly talented player like Joe Mixon, LeSean McCoy, or Nick Chubb will be forced to share the backfield as a rookie – usually due to some amount of veteran deference, or perhaps due to a lack of experience in pass protection (a go-to talking point among coaches). It is also possible for an RB to become more efficient as they further adjust to the NFL – Le’Veon Bell jumped from 3.5 to 4.7 YPC and from 1.22 to 1.73 YPRR after his rookie season. LaDainian Tomlinson (3.65) and Christian McCaffrey (3.72) also struggled as rookies. Players like Dalvin Cook were simply injured in Year 1 before exploding onto the scene once healthy. Finally, lackluster draft capital is a commonality among many RBs who did little as rookies but would go on to dominate later – Austin Ekeler and Aaron Jones combined for just 128 carries in their rookie seasons.

In our justifications, we can find parallels to players now entering Year 2 like Breece Hall (injury), James Cook, Kenneth Walker, and Dameon Pierce (shared backfields to differing extents), Isaiah Pacheco (poor draft capital), or even Rachaad White and Brian Robinson (inefficiency). Of course, not all players will break out (and therefore join our sample), but we can safely assume that Year 2 RBs have much better chances of doing so than older ones.

We can reveal more of what’s truly going on by plotting the season in which RBs first broke out (finished top-12), giving us a sense of breakout odds in each career year. While RBs can improve in their second season, it turns out a plurality of the sample first “broke out” as rookies. The vast majority did so at least by Year 2.

The upshot for dynasty leagues is that RBs who fail to break out after two years should be sold – particularly if they can be flipped for anything resembling top-12 RB prices. History shows these players are rather unlikely to provide multiple top-end seasons. Travis Etienne technically fits this bill – though with the massive asterisk that he didn’t have a chance to play a single snap in Year 1. Players entering Year 4, like J.K. Dobbins and D’Andre Swift, have even longer odds of ever breaking into the top-12 more than once.

Examining the overall sample regarding breakouts also provides further evidence that RBs who immediately capture their backfields as rookies should not be expected to improve their production in Year 2 as the first age curve implied. Among the sample, those who broke out (finished top-12) in Year 1 did not improve at all in Year 2 – actually scoring slightly fewer fantasy points than they did as rookies on average (about 11.3 fantasy points less over a full season).

This doesn’t apply to any of this year’s crop of sophomore RBs, but it is worth remembering to keep expectations in check the next time a Najee Harris immediately captures most of a backfield’s opportunity. Year 2 breakouts come from players that still have room to grow.

2023 Fantasy Takeaways

As mentioned previously, Year 7 is the first season in which RB production dips below the career baseline, while Year 8 is when the distribution of outcomes really spreads out – with many players nosediving towards total irrelevancy.

The storied RB class of 2017 is entering Year 7, most notably including Austin Ekeler, Christian McCaffrey, Joe Mixon, Aaron Jones, James Conner, Alvin Kamara, Leonard Fournette, and Dalvin Cook. Things don’t look great for much of this group – Fournette and Cook are without teams at the time of publishing, Kamara is potentially facing suspension, and only Ekeler, McCaffrey, and Mixon have not already taken a step back from RB1 production.

Since the age curves only reflect yearly averages, Ekeler and McCaffrey can certainly still be power law players. I’m mostly fine with Mixon’s discounted RB17 Underdog ADP. But all of them carry real risk of turning in a mediocre season by their standards – which, for Ekeler and McCaffrey, would saddle your roster with the massive opportunity cost of missing out on a Round 1 WR. Mind you, I’m still getting exposure to each (particularly to Ekeler within Chargers stacks), but proceed with caution.

The rest are largely volume plays at this point – which is fine given the deflated costs of Fournette and Cook in particular, but none are likely to catapult back to true difference-maker status. And none are the archetype of RB that wins fantasy leagues – 11 of the 12 most popular RBs on playoff rosters from 2017-2021 were in their first, second, or third season.

The only notable RBs entering Year 8 are Ezekiel Elliott and Derrick Henry. Zeke also has no team (for now), so it should be pretty clear where his career is trending. If you need any hints: among 42 RBs who carried the ball 100+ times in 2022, Elliott ranked 38th in YPC (3.8), 30th in explosive play rate (3.5%), 31st in success rate (47.6%), 35th in yards after contact/attempt (2.55), and 35th in missed tackles forced/attempt (0.14).

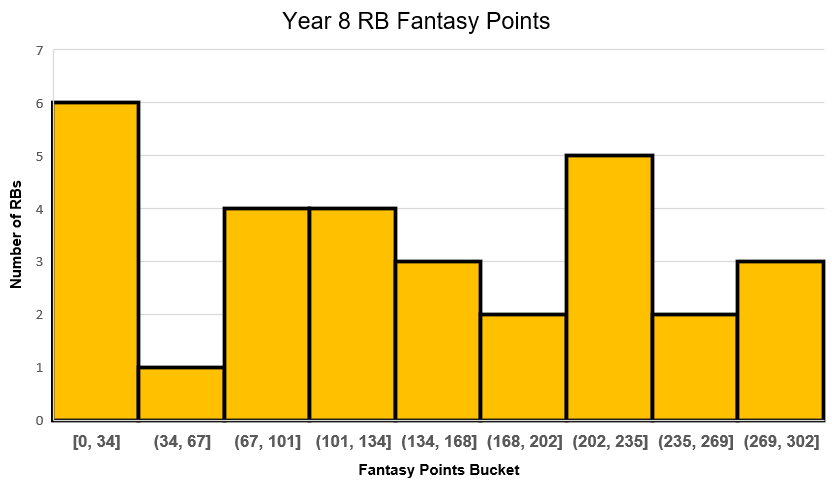

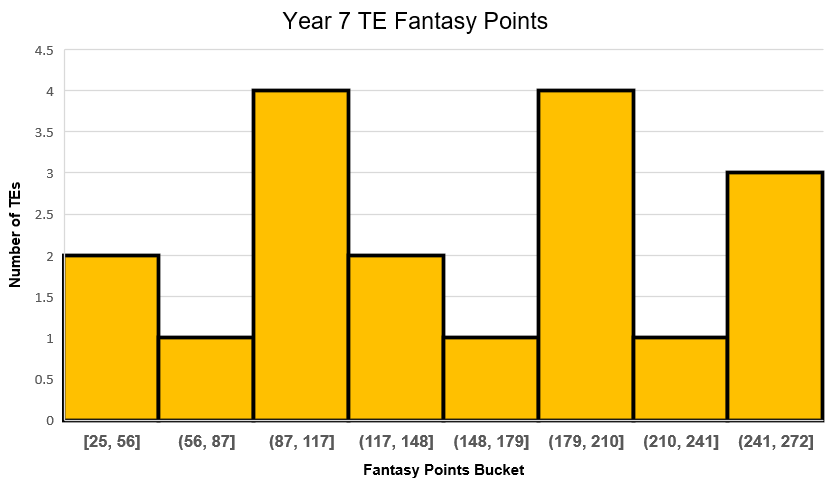

Henry is a trickier evaluation since Year 8 is the first season in which RB scoring becomes decidedly not normally distributed. Therefore, it would be a flagrant example of the ecological fallacy to assume Henry will score around 73% of the RB baseline in 2023 — because most Year 8 RBs don’t! Instead, Henry appears just as likely to either perform about as well as he always has (he’s averaged 281 fantasy points since 2019) or fall off a much steeper cliff – because the extreme ends of this distribution are just as (or more) populated than the middle.

Let’s look even closer at the most comparable players to Henry (production-wise). Henry had a top-5 score among the sample in Year 7. For the rest of Year 7's top-5, the average Year 8 score was 219 fantasy points – significantly better than most, but still below what you'd want from Henry's RB8 ADP (219 PPR points last year would have been the RB15). If Henry lands anywhere below the top few buckets on the above graph, he’s a catastrophic bust at cost.

Given the wide range of outcomes, I’m personally leaning toward avoiding Henry this year – not because I’m certain he’ll hit the wall, but because you can make less risky bets on similarly priced players like Josh Jacobs and Rhamondre Stevenson to similarly dominate touches on dysfunctional offenses.

If you take one thing away from this section, it should be to absolutely hammer RBs entering Year 2 – representing the largest seasonal upswing in average production and the most common breakout year for veterans. I’m especially partial to Breece Hall, who was absurdly hyper-efficient as a rookie and was well on his way to taking over to the tune of 66.4% of the backfield’s XFP in Weeks 3-6 – which would have ranked top-10 if over the full season.

🚨NSFW Breece Hall stats🚨

— Ryan Heath (@QBLRyan) May 31, 2023

Among RBs with 80+ routes in 2022, Breece Hall finished:

- 2nd in YPRR (between Henry and CMC)

- 3rd in TPRR (between Ekeler and Swift)

- 1st in missed tackles forced/reception

- 1st in TOTAL air yards (CMC was 2nd, had 14 fewer on 257 more routes)

My preferred sophomore sleeper is James Cook, who similarly jumps off the page in efficiency and has little standing between him and a supermajority of backfield targets. The only credible competition the Bills have brought in is Damien Harris, who has never commanded more than 23 targets in a season. The team also still lacks a true second WR behind Stefon Diggs. Plenty of targets are ripe to be earned, with Devin Singletary leaving behind 52.

While running back targets are normally depressed in offenses featuring mobile QBs, Josh Allen’s check-down rate (8.8%) ranked first among QBs with 80+ rushing attempts last year. Of those teams, the Buffalo Bills’ 36.4 pass attempts per game also ranked first by far – with the next-closest Philadelphia Eagles averaging 5.2 fewer attempts per game. If any mobile QB can support volume for a receiving back, it is Allen – and the Bills’ well-chronicled previous attempts to add a backfield pass-catcher are further evidence of their desire for Allen to stay put and check down more. After the trade deadline last year, it was Cook – not the acquired Nyheim Hines – who gradually began stealing routes from Singletary.

Wanted to see how much truth there was to the idea that mobile QBs do not check down as often.

— Ryan Heath (@QBLRyan) June 15, 2023

Seems generally true, but a few interesting takeaways:

- Allen and Murray check down at the median rate, despite running a lot more

- Trevor Lawrence explains a lot about Etienne pic.twitter.com/rznWME2pjx

Cook was an accomplished receiver in college, and then impressed as a rookie, ranking top-12 among qualifying RBs in YPRR last year. Even if he’s subbed out for bigger bodies at the goal line, Cook can do serious damage at his RB30 ADP by earning more volume in Year 2, as we’ve demonstrated RBs often do.

Missed tackles forced/touch vs. yards per opportunity — reposting to highlight RBs entering Year 2 in red.

— Ryan Heath (@QBLRyan) May 27, 2023

I couldn’t tell you how he sees volume, but I can’t get Jaylen Warren out of my head. pic.twitter.com/67Fe7AVk7U

I would not entirely count out any Year 2 RB – even Rachaad White and Brian Robinson have plausible excuses for their inefficiency that we could easily use to post hoc rationalize a Year 2 breakout. Tampa Bay’s offensive line ranked 28th in yards before contact per attempt and 31st in ESPN’s run block win rate, and Leonard Fournette did not fare much better than White – who now has virtually no backfield competition. Robinson was shot in the leg just weeks before taking the field, so it’s tough to fault him for failing to break many tackles. Crazier things have happened than players like these two becoming fantasy football mega-producers.

Wide Receivers

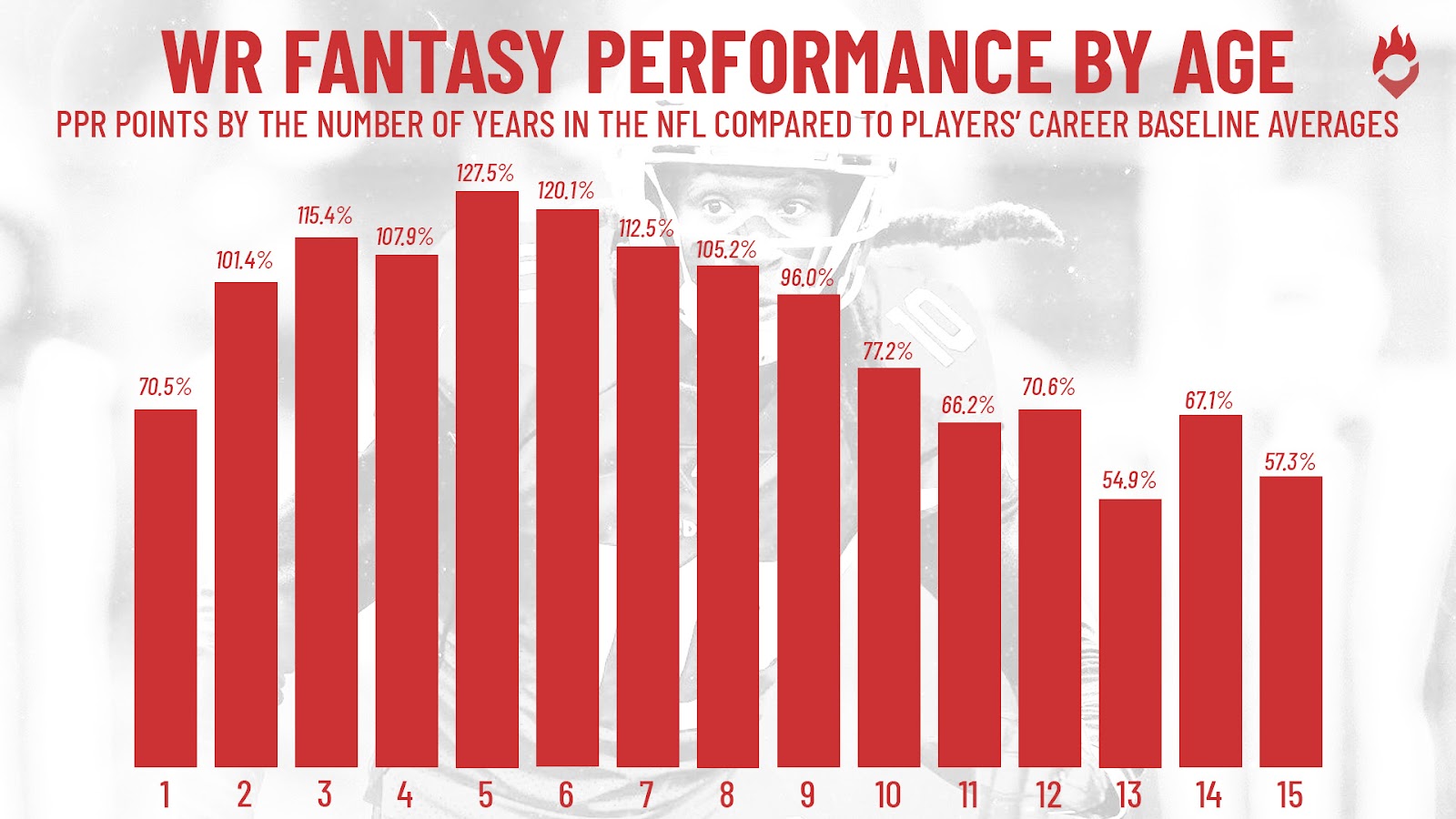

Key Takeaway: WRs typically underwhelm as rookies, before making a big leap in their sophomore season. (WRs generally “break out” in Year 2 or Year 3). Unlike at RB, WRs gradually improve through Year 5, their best season on average. A slow regression to the career baseline occurs in Years 6-9, with a sharper drop to rookie-level production occurring in Year 10. Individual outcomes sharply diverge from the charted average in Year 11, as players either remain relatively productive or fall to near-zero production – with few in between.

In dynasty leagues, the danger begins even earlier. Our sample size shrinks from 33 players in Year 8 to just 25 in Year 10, meaning about one-quarter (24%) left the league in that timespan. And remember, I have only included multi-year top-12 producers – not random scrubs. No matter how good your WR entering Year 8 has been, the data suggests there is a real chance he retires and leaves your dynasty team hanging within two years. Allen Robinson could become the latest example if he fails to make Pittsburgh’s roster this year.

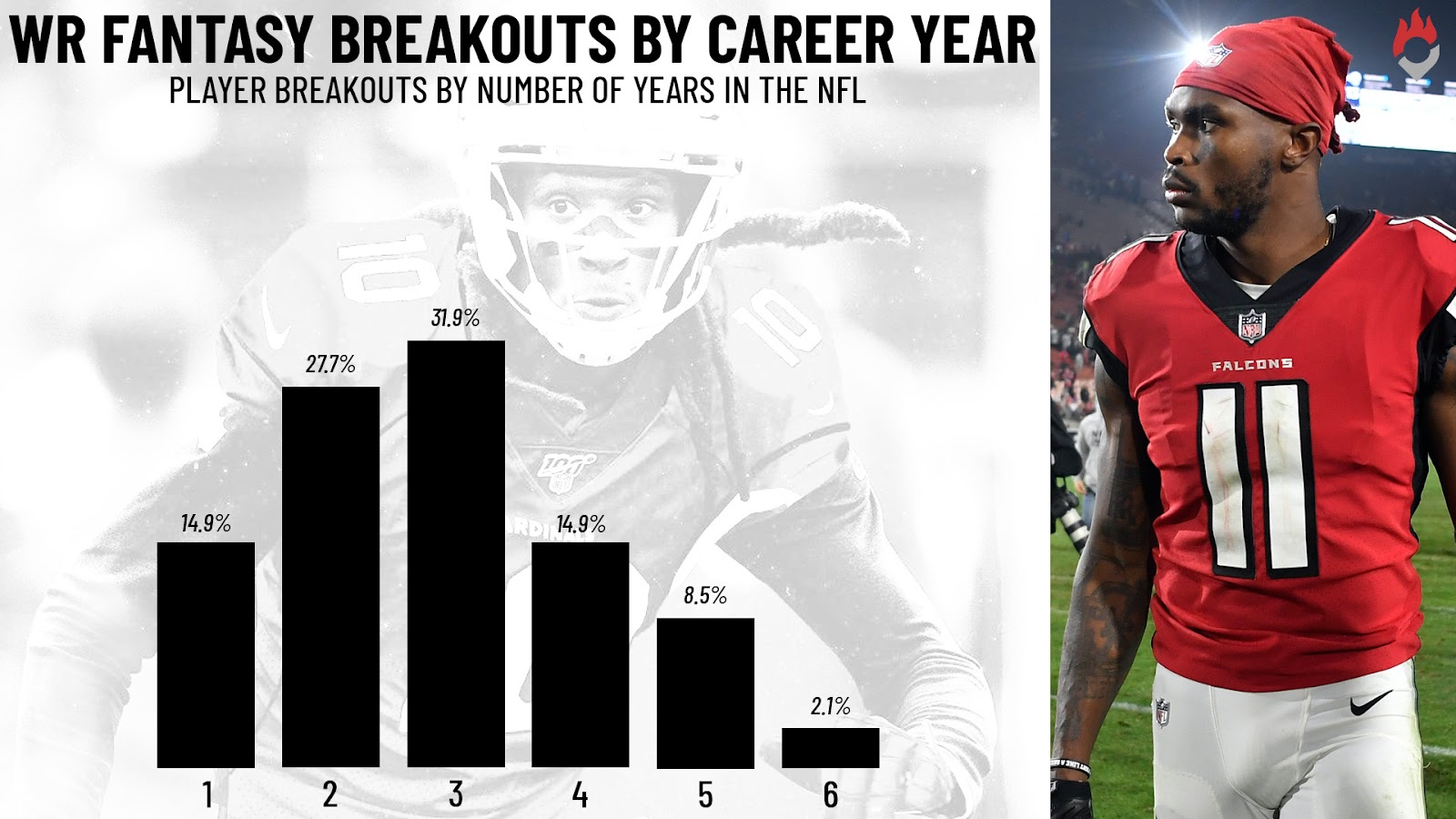

Let’s get to the fun part. What about early-career breakouts?

As you might expect, top-12 WR breakouts occurred overwhelmingly in Years 2 and 3. The fantasy football takeaway is simple – target Year 2 and 3 WRs in hopes they exceed expectations. Indeed, my study from last year demonstrated sophomore WRs are ADP values in the middle rounds at much higher rates than other WRs.

Rookie season breakouts may be becoming more common. Year 1 accounted for just 7% of breakouts pre-2014, but 26% of breakouts since. Years 2 and 3 each accounted for 36% of breakouts before 2014, but just 16% and 26% (respectively) from 2014 to today.

But we’re now splitting into very small sub-samples (greatly affected by ebbs and flows in draft class quality), so don’t treat those split percentages as gospel. Additionally, the sample only includes players with multiple top-12 seasons, so recent Year 2 breakouts like Jaylen Waddle, Amon-Ra St. Brown, and DeVonta Smith could soon join – and one could say the same about recent Year 3 breakouts like Deebo Samuel, Diontae Johnson, and CeeDee Lamb. This is all to say that it’s not too late for Fantasy Points favorite Elijah Moore.

Highest YPRR vs Cover 2 over the last two seasons, min 120 routes:

— Football Insights 📊 (@fball_insights) March 23, 2023

Brandin Cooks - 2.64

DJ Moore - 2.62

Tyreek Hill - 2.46

Jaylen Waddle - 2.43

Elijah Moore - 2.20

Zach Wilson was the NFL’s least accurate within 10 yards (59%)

2023 Fantasy Takeaways

WRs entering Year 10 or later of their career include Davante Adams, DeAndre Hopkins, Keenan Allen, Mike Evans, and Brandin Cooks. This is not a reason in itself to fade any of these players, but they are all exposed to more risk than it may appear on the surface. And for most of them, that’s adding on to many other risks – only Allen will enter the season with the same QB as in 2022, and Hopkins is without a team in June after posting his two lowest YPRR seasons since that odious time he had to play with Brock Osweiler.

Over the last two seasons, Evans has played with the greatest QB of all time and enjoyed two of the top-four most pass-heavy offenses since at least 2010. Tampa Bay’s likely Week 1 starter is Baker Mayfield, who averages 31.4 pass attempts per game in his career, a number which would have ranked 24th among NFL teams last season. The Buccaneers also led the NFL in red-zone dropback rate last season – a mark that a Tom Brady-less Bucs team is unlikely to reach, depriving Evans of the scoring opportunities he’s made his career on.

Obviously, Garrett Wilson, Chris Olave, Ja’Marr Chase, and Amon-Ra St. Brown are 2nd- and 3rd-year WRs who should be incredible in fantasy this year, and their ADPs reflect that. But we can more actionably take advantage of the Years 2-3 breakout trend (for redraft) in the cases of players like Christian Watson, Drake London, Treylon Burks, Jahan Dotson, Rashod Bateman, or Elijah Moore.

Rookie season YPRR is extremely predictive of future fantasy success for WRs:

— Ryan Heath (@QBLRyan) May 30, 2023

- Wilson/Olave/London/Watson/Burks in pretty good company

- Dotson and Pickens chilling in the middle (unlabeled)

- I will never “buy low” on players like Bell and Thornton pic.twitter.com/UP7clin2wX

Rather than recycle material, I’ll just implore you to review my recent article on sophomore WRs. (Seriously, you’re going to want to re-read this piece. This is a uniquely stacked class of sophomore WRs, and I view several of these names as potential or likely league-winners.) Beyond the players discussed in that article, I’ll also add for your consideration Kadarius Toney (who would have been right next to A.J. Green on the above chart if he’d run only four more routes to qualify), Wan’Dale Robinson (better TPRR than Justin Jefferson and better YPRR than Jaylen Waddle posted as rookies), and Nico Collins (just led Houston in YPRR and TPRR, is the only clear outside WR on the team, and will have the second overall pick throwing him the ball this year).

Naturally, those are only the players I personally prefer. I won’t fault anyone for throwing darts at the likes of Isaiah Hodgins, Jameson Williams, George Pickens, or John Metchie.

Tight Ends

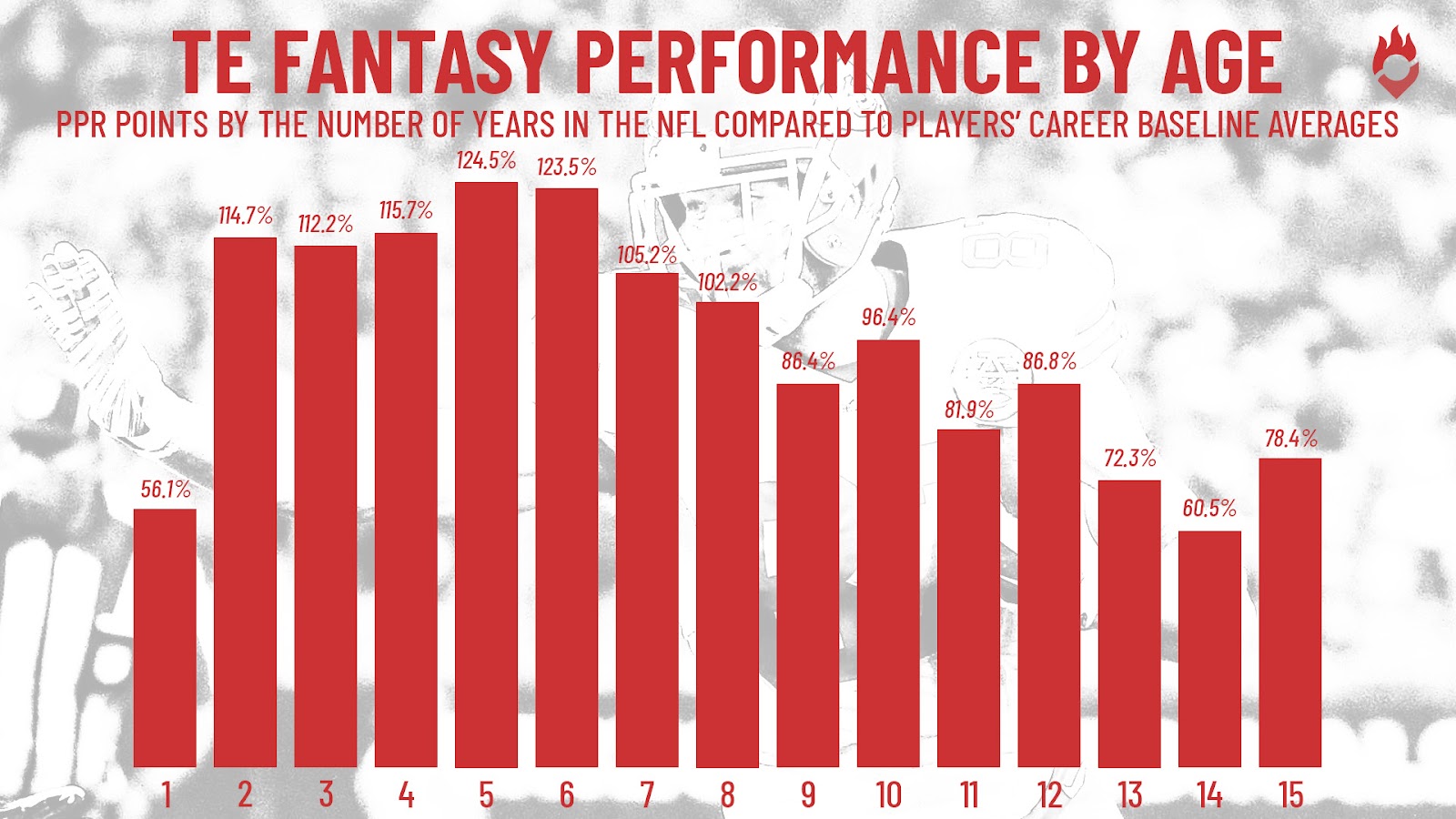

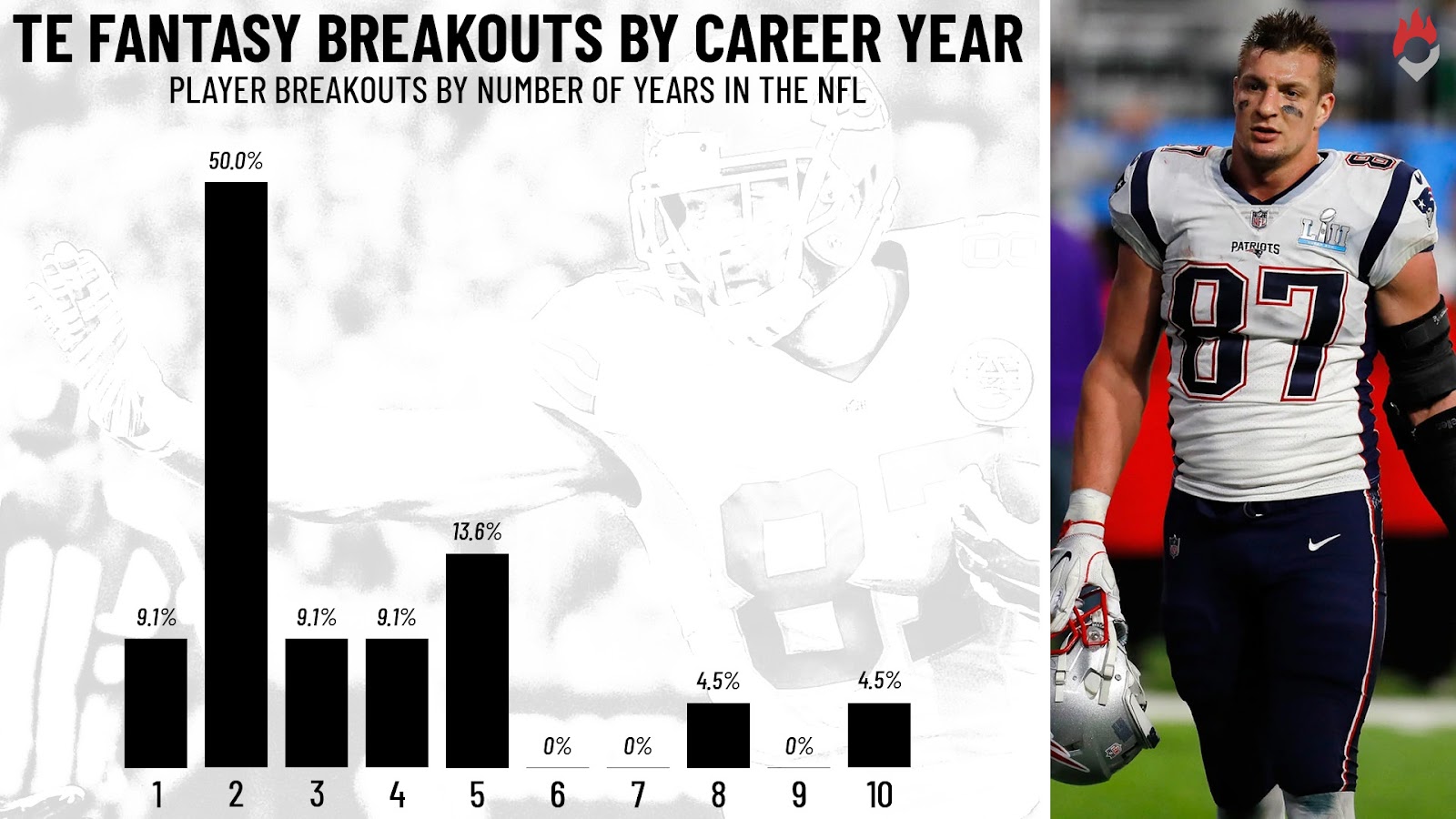

Key Takeaway: The sophomore TE breakout is among the most powerful and reliable laws of fantasy. Typically, they hover around this baseline for two more years before hitting their peak seasons in Year 5 and Year 6. A steep decline begins in Year 7, when the curve becomes a bit misleading.

As proof of that last statement, the TE scoring distribution becomes a Lovecraftian abomination in Year 7. The average (152 fantasy points) isn’t very close to how most of the players actually performed. Past this point, TEs will survive or die entirely on the merits of their own talent and resilience, with their production largely untethered from an aging curve.

This reveals two truths: 1) that it is exceedingly impressive that Travis Kelce has made it through 10 seasons and is still by far the position’s top producer, and 2) that the “81.9% production average for Year 11 TEs” has little meaning for Kelce, and should not prevent us from drafting him at his Round 1 ADP.

Kelce just commanded the most targets of any season in his career, and he has posted his two highest-ever route shares over the last two seasons. 2022 was his fifth-best year (out of nine) in YAC/R – so it doesn’t seem like his athleticism is waning. Last year’s 2.23 YPRR also tied for the third-best of his career.

Could Kelce suddenly and sharply decline in his 11th season? Harstad’s mortality table hypothesis necessitates the possibility, and Jason Witten has the best Year 11 season in our sample with just 206.1 PPR fantasy points – only 65% of what Kelce accomplished last season. But then again, Kelce had by far the best Year 10 score in the sample – Witten’s Year 10 was only 73% of Kelce’s. There is no recent TE as productive as Kelce so late into his career to which we can draw a comparison – he’s a cut above even Tony Gonzalez, who managed to finish as the TE2 in his 11th season. Jerry Rice (if he were a TE) is probably a closer parallel.

Considering that Kelce’s 3.03 WAR (wins above replacement) was top-5 among all players and more than double that of the next tight end last season, the reward for drafting him in any year in which he keeps it up is massive. Given that he’s survived this long against such insurmountable odds, he’s unquestionably earned my benefit of the doubt. Even by the Harstad model, he likely has at least one more year of his prime left at 33 years old.

By and large I think people overpredict declines among older players. (And RBs of all ages!)

— Adam Harstad (@AdamHarstad) November 17, 2021

Here's the "expected prime years remaining" tables I use for (good) NFL players based on observed aging patterns of their (good) positional predecessors. https://t.co/sFygYprRQ1 pic.twitter.com/ZZ9djlBtAZ

An insane number of top-6 TE breakouts occur in Year 2 – again, targeting Year 2 TEs is one of the most potent and enduring cheat codes in all of fantasy, especially given the apathy most drafters hold for the position. Among players who would go on to post another top season, Year 3-5 WR breakouts have occurred much more commonly than Year 3-5 TE breakouts.

That may sound dicey for Kyle Pitts, but he technically already broke out as a top-6 TE in his rookie season. I urge the reader – do not fade Pitts. If you need something to set you straight, I recommend Graham Barfield’s excellent thinkpiece in which – among other great nuggets – you can be reminded that Pitts underperformed his XFP by 4.6 FPG last year, making him the league’s most unlucky TEs. There are also ridiculous stats like this one:

Kyle Pitts is already a top-5 outside WR in the NFL

— Scott Barrett (@ScottBarrettDFB) May 29, 2023

YPRR Leaders, Routes Run from Out-Wide

+min. 150 routes from out-wide [2021-2022]

1. A.J. Brown (3.16)

2. Tyreek Hill (3.07)

3. Amon-Ra St. Brown (2.74)

4. Kyle Pitts (2.73)

5. Justin Jefferson (2.58)

6. Davante Adams (2.57)

2023 Fantasy Takeaways

As we’ve learned, targeting Year 2 TE breakouts pays handsomely. We have an exciting group of sophomore TEs going much later in drafts with the potential to continue the trend this year.

Among tight ends who ran 100 or more routes and caught 25 or more passes, Chigoziem Okonkwo just led the league in missed tackles forced per reception (0.34), YPRR (2.85), and YAC/R (8.0). That was one of the best YPRR seasons by any TE since 2009. Chig is an easy smash in the double-digit rounds (ADP: TE12) and by far the most intriguing Year 2 TE option.

We can predict career outcomes for TEs using rookie season YPRR and SPORQ athleticism score from @ScottBarrettDFB

— Ryan Heath (@QBLRyan) June 5, 2023

- Chig has a sky-high ceiling

- Dulcich not quite as appealing

- Kelce would be between Gronk and Chig if using 2014 (first season w/ a snap)

Hit rates below 👇🏻 pic.twitter.com/qmT82nqlRu

I’ll also ask you to turn your attention to Greg Dulcich, who had a historically productive rookie season to go along with an impressive 30.0 routes per game (4th among TEs). He’s even more affordable than Okonkwo at his TE15 Underdog ADP.

Most Receiving Yards/Game

— Ryan Heath (@QBLRyan) June 2, 2023

[Rookie TEs since 2010 + min. 8 games]

1) KYLE PITTS (60.4)

2) Jordan Reed (55.4)

3) Evan Engram (48.1)

4) GREG DULCICH (41.1)

5) Aaron Hernandez (40.2)

…

10) Mark Andrews (34.5)

11) George Kittle (34.3)

12) Rob Gronkowski (34.1)

Note: Adam Trautman…

It doesn’t hurt that new HC Sean Payton already seems infatuated with Dulcich – leading him to wax poetic about Jeremy Shockey, Jason Witten, and Jimmy Graham.

High praise from Sean Payton on second year TE Greg Dulcich and his possible role as the joker in this #broncos offense. A role filled by a RB or TE that creates mismatches on the field and has been filled by really talented players in the past for Payton. pic.twitter.com/hdlKygUiod

— James Palmer (@JamesPalmerTV) June 1, 2023

Jelani Woods (ADP: TE33) also makes a surprise appearance in the top-right of the above chart – which boasts a 48% top-6 hit rate. Woods is a freak athlete (88.4 SPORQ) who caught 8 of 9 targets for 98 yards in the one game he cleared a 60% route share last year. Woods was not on my radar at all before researching for this piece. He should be on yours now.

Don’t forget about Isaiah Likely. In games where Mark Andrews had less than an 80% route share, Likely averaged a team-leading 22% target share and 68.0 YPG. The Baltimore Ravens’ offseason acquisitions at WR suggest they intend to play more 11-personnel under their new OC, but Likely (ADP: TE28) could be an elite (and the only) handcuff TE with Underdog tournament-winning upside if Andrews were to suffer an injury.

In college, Isaiah Likely had some of the most insane stats I've ever seen from a TE

— Scott Barrett (@ScottBarrettDFB) June 15, 2023

[1]

As a rookie, Isaiah Likely was once again really statistically impressive

[2] pic.twitter.com/HfRz0ruFgK

I’m somewhat less excited about Trey McBride – who ranked 32nd among 38 qualifying TEs in YPRR last season. McBride was at least highly productive in college – he averaged 2.84 yards per team pass attempt in 2020, and 2.83 in 2021. At the time, those numbers ranked best and 3rd-best among all TEs since at least 2000. McBride could see an opportunity this year with DeAndre Hopkins off the team and Zach Ertz recovering from a late-season ACL/MCL injury. However, McBride averaged a 13% target share with Ertz sidelined. And his 0.84 YPRR ranks 3rd-worst among rookie TEs who ran 200+ routes since at least 2010 (the other two were fellow sophomore Cade Otton and Tommy Tremble).

Moving away from the sophomore TEs (but not really), I’m obligated to point out that rookie Dalton Kincaid’s current TE11 ADP on Underdog – above Okonkwo and Dulcich – is completely preposterous. If every chart in this section isn’t proof enough, consider that only four rookie TEs since 2010 have averaged just 10+ FPG (Jordan Reed, Evan Engram, Kyle Pitts, and Aaron Hernandez). 12 sophomores (about one per year) have done so over 8+ games.

Year 7 is both the beginning of the TE danger zone and a year in which breakouts are exceedingly rare. This means we can probably give up on David Njoku and his TE9 ADP, having never exceeded 650 receiving yards or 4 TDs in any of his six seasons. Njoku was at his most effective in the slot last season (1.86 slot YPRR vs. 1.48 inline), but he could be in danger of losing those looks to Elijah Moore – who will certainly provide tougher competition than David Bell.

George Kittle (TE4) and Evan Engram (TE8) are also entering Year 7. I already wasn’t particularly excited to pay up for either considering the additional target competition each face with Deebo Samuel and Calvin Ridley now healthy and available, and the risk of an age-based production dropoff gives me additional pause on both players. While Engram just had an efficiency upswing, Kittle’s 1.97 YPRR in 2022 was his worst since his rookie season. And if Kittle is going to come close to paying off his ADP, he needs to be hyper-efficient – thanks to San Francisco’s hyper-run-heavy offense, Kittle’s 25.9 routes per game ranked just 14th at the position in 2022 and far behind players like T.J. Hockenson (31.5) and Greg Dulcich (30.0). Both Kittle and Engram also have their own extensive histories of lower-body injuries – not encouraging signs for longevity.

Kyle Pitts rightfully occupies most of our headspace among Year 3 TEs, but Pat Freiermuth could also be on his way to a slightly delayed top-6 breakout. Freiermuth ranks 9th among TEs in FPG (9.4) over the last two seasons, ahead of Pitts’ 9.3, who ranks 12th. Excluding a Week 5 game he left early due to injury last year, Freiermuth averaged 6.4 targets per game (20.4% target share) and 48.0 YPG. He was only 3.9 YPG shy of Diontae Johnson for the team-high, and among all TEs, those numbers ranked 5th-best and 6th-best.

I’ll leave you by mentioning that Cole Kmet (entering Year 4) is still technically in a semi-plausible breakout window. Kmet averaged 12.9 FPG over his last 7 games with Justin Fields under center, which would have ranked 3rd-best among TEs if over the full season. His 28.2% YMS and 50% TDMS over this span would have ranked 2nd-best and best among TEs, or 16th- and 2nd-best among WRs. Among Chicago’s six WRs/TEs who ran over 100 routes, Kmet was also by far the best in depth-adjusted yards per target over expected (0.9, next-best was Equanimeous St. Brown’s 0.0) as well as missed tackles forced per reception (0.18, to 0.11 from Dante Pettis).

Worried about D.J. Moore? Don’t be. Moore is much more likely to crowd out targets that previously went to players like Darnell Mooney, as Moore’s aDOT was 12.9 to Kmet’s 6.1 last year. No qualifying Bears WR/TE aside from Kmet had an aDOT lower than 9.0 – he seems to be the only player Justin Fields trusts on shallower routes. I would not prioritize him over Okonkwo or Dulcich, but Kmet at his TE14 Underdog ADP isn’t a bad late sleeper, especially in a top-heavy tournament-style format as an affordable stacking partner for Fields.